An Approach to Teacher Training Based on the ‘Technological’ Content of Primary Science Education

Received: 06/21/2022

Accepted: 09/10/2022

DOI: 10.11621/nicep.2022.0202

To cite this article:

Vysotskaya, E. V. , Lobanova, A. D., Yanishevskaya, M. A., Khrebtova, S. B. (2022). An Approach to Teacher Training Based on the ‘Technological’ Content of Primary Science Education. New Ideas in Child and Educational Psychology, 2 (1-2), 49-65. DOI: 10.11621/nicep.2022.0202

Background. The effort to make students literate has guided many studies, in particular those concerning teacher training. A number of researchers note the importance of integration between teaching literacy and teaching sciences – especially in primary education. According to Developmental Instruction Theory, the content of learning is vital and, if revised and designed carefully, it may provide for deep conceptual knowledge. The introductory curriculum for natural science that we developed based on the Cultural-Historical and Activity approach is based on reconstructing the origins of concepts through supporting students’ own inquiry-based activity within a “technological” framework. Our educational module demands new skills from teachers, which they could not have acquired from common teacher training or from their own teaching experience in post-secondary school.

Objective. As we aimed to provide sound support for teachers who will be teaching our module on natural sciences, the transmission of the Activity approach to teaching evolved into a research study.

Design. In this paper we present a way to train teachers, according to which teachers participate from two vantage points simultaneously: that of a student and that of a curriculum designer. Working with our educational module demands transitions within the text–lab–task triad as the major context for treating special educational texts. Teachers have to identify connections between two transparent lines of the module’s content: the “technological” line, which presents the storyline and provides the meaningful framework, and the “conceptual” line: the evolution of modeling that provides for students’ comprehension. Teachers have the opportunity to conceive of the idea behind each course excerpt as part of the major conceptual development and as a support for mastering basic literacy skills. As we performed three cycles of our teacher training (12 participants in total), we collected discussion, feedback, teachers’ diagrams, etc., and analyzed them in their entirety. We used a text on iron production to illustrate our approach and the teachers’ progression.

Results. Our experience in teacher training through examination of the origin of concepts in natural science results in a teacher’s ability to design the trajectory of students’ progress through the introductory curriculum. Teachers thus learn to plan and conduct their own sequence of lessons, which will scaffold students’ initiative, and to adjust the flow of the class discussion smoothly.

Conclusion. The principles of the organization of the teachers’ learning activity that we outline show how teachers can implement and promote the Activity approach to primary science education.

Highlights- The new introductory module for the natural sciences, designed according to the Activity and Cultural-Historical approach, requires teachers to support students’ own inquiry.

- The new approach to teacher training suggests that teachers read the educational texts and devise the diagrams, as their students will also do, but the teachers have to mark the text fragments where their students will find the clues for their modeling, and thus, reveal the intention of module’s design.

- Our experimental teacher training showed that teachers learned to plan and conduct their lessons, consciously adapting the flow of the classroom work to students’ own progress, which they could identify according to the two lines of the module content: the “technological” and the “conceptual.”

Актуальность. Современные подходы к обучению учителей предусматривают необходимость формирования функциональной грамотности учащихся средствами всех учебных предметов, как в начальной школе, так и в следующих классах. В рамках теории развивающего обучения эта проблема рассматривается в более широком контексте владения учителем технологией формирования понятийного (теоретического) мышления. Наибольшее внимание здесь уделяется пересмотру дидактических позиций, с которых производится отбор содержания учебного предмета. Разработка пропедевтического курса природоведения в традиции культурно-исторического и деятельностного подходов в обучении потребовала реконструкции условий происхождения научных понятий в особом «технологическом» контексте развития материальной культуры человечества. Новое содержание учебного предмета, ориентированное именно на формирование функциональной грамотности учащихся предполагает наличие у учителей специфических умений, которые, к сожалению, не приобретаются ими в ходе их собственного обучения в старшей школе или в педагогическом вузе в традиционном порядке ознакомления с естественнонаучным материалом.

Цель. В ходе подготовки учителей к преподаванию нашего курса природоведения освоение ими основ культурно-деятельностного подхода к выбору содержания и методов обучения выдвинулось на первый план, как ведущая цель, требующая особого анализа и разработки средств ее достижения.

Дизайн. В этой статье мы предлагаем подход к обучению учителей, в котором содержание обучения рассматривается учителями одновременно с двух позиций: с позиции учащегося и с позиции разработчика. Учебная деятельность учащихся в рамках пропедевтического модуля «О чем расскажут естественные науки?» подразумевает постоянные переходы между разными способами работы с учебным текстом, опробованием некоторых частей «древних» технологий на лабораторном столе и поиском решения задач, приведенных в учебном пособии. Задачей подготовки учителя здесь становится поиск и реконструкция связей между двумя ведущими, «сквозными» линиями развития предметного содержания: «технологической», которая задаёт последовательность освоения школьниками содержания курса как осмысленную и целенаправленную, и «понятийной», представляющей собой развитие требуемого способа учебного моделирования, опосредствующего понимание учебного текста и приложения его к опытно-исследовательской практике. Учителю следует понимать место каждого фрагмента курса в развитии понятийной (функциональной) грамотности учащихся и научиться поддерживать соответствующее учебное продвижение учащихся в его содержании. В ходе проведения трёх обучающих сессий с учителями (12 участников) протоколы обсуждений, обратная связь, учительские рисунки, схемы и чертежи и пр. использовались как материал анализа прогресса участников и тем самым эффективности обучения. Для иллюстрации подхода к обучению учителей и соответствующего продвижения учителей в учебном содержании модуля мы выбрали фрагмент, посвященный формированию ряда теоретических представлений о получении металлов из их природных источников.

Результаты. Наш опыт подготовки учителей путём погружения их в работу с условиями происхождения понятий в естественных науках показал, что такой подход перспективен. Важным результатом является возможность учителей самостоятельно проектировать траекторию развития своих учащихся, поддерживая их учебное продвижение в содержании пропедевтического курса. Учителя учатся планировать и проводить уроки, которые поддерживают инициативу учащихся, выбирая фрагменты учебных текстов и заданий в поддержку живой общеклассной дискуссии, вызывающей содержательный интерес.

Вывод. Намеченные нами принципы организации обучения самих учителей служат тому, чтобы учителя смогли полагаться на культурно-деятельностный подход, как содержательную и методическую основу преподавания начального естествознания в школе, закладывающего основы функциональной грамотности учащихся для будущего изучения основ наук.

Ключевые положения- Пропедевтический курс природоведения, реализующий основные принципы культурно-исторического и деятельностного подходов в обучении, требует от учителей понимать место каждого фрагмента курса в развитии понятийной (функциональной) грамотности учащихся и поддерживать соответствующее учебное продвижение учащихся в его содержании.

- Новый подход к обучению учителей предлагает учителям рассматривать содержание обучения как с позиции ученика, так и с позиции разработчика. Это предполагает как разбор учебных текстов с использованием необходимых для его понимания знаково-модельных средств, так и «методическую разметку» фрагментов учебного пособия в соответствии с тем, в какую понятийную и технологическую линию они должны встраиваться на уроке.

- Важным результатом является возможность учителей самостоятельно проектировать траекторию развития своих учащихся, поддерживая их учебное продвижение в содержании пропедевтического курса.

Introducción. El esfuerzo por alfabetizar a los estudiantes guio muchos estudios, en particular, los relacionados con la formación de profesores. Varios investigadores señalaron la importancia de la integración entre la enseñanza de la alfabetización y la enseñanza de las ciencias, especialmente en la educación primaria. De acuerdo con la Teoría de la Educación Desarrolladora, el contenido del aprendizaje es vital y, si se revisa y diseña con cuidado, puede proporcionar un conocimiento conceptual profundo. El plan de estudios de introducción a las ciencias naturales que desarrollamos con base en el enfoque Histórico-Cultural y de Actividad se basa en la reconstrucción de los orígenes de los conceptos mediante el apoyo a la propia actividad basada en la indagación de los estudiantes dentro de un marco "tecnológico". Nuestro módulo educativo exige nuevas habilidades de los docentes que no habrían podido adquirir durante la formación docente común o de su propia experiencia docente en la escuela postsecundaria.

Objetivo. Dado que nuestro objetivo era proporcionar un apoyo sólido a los profesores que impartirían nuestro módulo sobre ciencias naturales, la transmisión del enfoque de la actividad a la enseñanza evolucionó hasta convertirse en un estudio de investigación.

Diseño. En el presente trabajo exponemos una forma de educar a los docentes, según la cual ellos participan desde dos puntos de vista simultáneamente: el de estudiante y el de diseñador curricular. Trabajar con nuestro módulo educativo exige transiciones dentro de la tríada texto-laboratorio-tarea como el contexto principal para tratar textos educativos especiales. Los profesores deben identificar las conexiones entre dos líneas transparentes del contenido del módulo: la línea "tecnológica", que presenta la historia y proporciona el marco significativo, y la línea "conceptual": la evolución del modelado que proporciona la comprensión de los estudiantes. Los maestros tienen la oportunidad de concebir la idea detrás de cada extracto del curso como parte del desarrollo conceptual principal y como apoyo para dominar las habilidades básicas de alfabetización. Como realizamos tres ciclos de nuestra formación docente (12 participantes en total), recopilamos debates, comentarios, diagramas de docentes, etc., y los analizamos en su totalidad. Usamos un texto sobre la producción de hierro para ilustrar nuestro enfoque y la progresión de los maestros.

Resultados. Nuestra experiencia en la formación de los maestros a través del examen del origen de los conceptos en ciencias naturales da como resultado la capacidad de un docente para diseñar la trayectoria del progreso de los estudiantes a través del plan de estudios introductorio. De este modo, los profesores aprenden a planificar y conducir su propia secuencia de lecciones, lo que servirá de andamiaje para la iniciativa de los estudiantes y a ajustar el flujo de la discusión en clase sin problemas.

Conclusión. Los principios de la organización de la actividad de aprendizaje de los docentes que describimos muestran cómo los docentes pueden implementar y promover el enfoque de la actividad en la educación científica primaria.

Destacados- El nuevo módulo de introducción a las ciencias naturales, diseñado según el enfoque Histórico-Cultural y de Actividad requiere que los docentes apoyen la propia indagación de los estudiantes

- El nuevo enfoque de la formación docente sugiere que los docentes lean los textos educativos y elaboren los diagramas, como también lo harán sus alumnos, pero los docentes tienen que marcar los fragmentos de texto donde sus alumnos encontrarían las pistas para su modelación, y así revelar las intención del diseño del módulo.

- Nuestra formación docente experimental mostró que los profesores aprendieron a planificar y realizar sus clases adaptando conscientemente el flujo del trabajo en el aula al propio progreso de los estudiantes, que podían identificar de acuerdo con las dos líneas del contenido del módulo: el "tecnológico" y el "conceptual."

Origines. Les efforts d'alphabétisation des élèves ont stimulé de nombreuses études, notamment celles concernant la formation des enseignants. Un grand nombre de chercheurs notent l'importance de l'intégration entre l'enseignement de la littératie et l'enseignement des sciences – en particulier dans l'enseignement primaire. Selon la théorie de l'instruction développementale, le contenu de l'apprentissage est vital et, s'il est révisé et conçu avec soin, il peut fournir des connaissances conceptuelles approfondies. Le programme d'introduction aux sciences naturelles que nous avons développé sur la base de l'approche culturelle-historique et d'activité est basé sur la reconstruction des origines des concepts en soutenant l'activité d'investigation des étudiants dans un cadre "technologique". Notre module pédagogique exige de la part des enseignants de nouvelles compétences qu'ils n'auraient pas pu acquérir dans le cadre d'une formation pédagogique commune ou de leur propre expérience d'enseignement au niveau postsecondaire.

Objectif. Comme nous voulions bien soutenir les enseignants qui enseigneront notre module sur les sciences naturelles, la transmission de l'approche pédagogique par l'Activité s'est transformée en une étude de recherche.

Conception. Dans cet article, nous présentons une manière de former les enseignants, selon laquelle les enseignants participent à partir de deux points de vue simultanément : celui d'un étudiant et celui d'un concepteur de curriculum. Travailler avec notre module éducatif exige des transitions au sein de la triade texte-laboratoire-tâche en tant que contexte majeur pour le traitement de textes éducatifs spéciaux. Les enseignants doivent identifier des liens entre deux lignes transparentes du contenu du module : la ligne « technologique », qui présente le scénario et fournit le cadre significatif, et la ligne « conceptuelle » : l'évolution de la modélisation qui permet la compréhension des étudiants. Les enseignants ont la possibilité de concevoir l'idée derrière chaque extrait de cours dans le cadre du développement conceptuel majeur et comme support à la maîtrise des compétences de base en littératie. Au cours de nos trois cycles de formation d'enseignants (12 participants au total), nous avons recueilli des discussions, des retours, des schémas d'enseignants, etc., et les avons analysés dans leur intégralité. Nous avons utilisé un texte sur la production de fer pour illustrer notre approche et la progression des enseignants.

Résultats. Notre expérience dans la formation des enseignants par l'examen de l'origine des concepts en sciences naturelles se traduit par la capacité d'un enseignant à concevoir la trajectoire de progression des élèves tout au long du programme d'introduction. Les enseignants apprennent ainsi à planifier et à conduire leur propre séquence de cours, qui étaiera l'initiative des élèves, et à ajuster le flux de la discussion en classe en douceur.

Conclusion. Les principes d'organisation de l'activité d'apprentissage des enseignants que nous exposons montrent comment les enseignants peuvent mettre en œuvre et promouvoir l'approche par l'activité dans l'enseignement des sciences au primaire.

Points principaux- Le nouveau module d'introduction aux sciences naturelles, conçu selon l'approche Historico-Culturel et de l`Activité, demande aux enseignants de soutenir la propre recherche des élèves.

- La nouvelle approche de la formation des enseignants suggère que les enseignants lisent les textes pédagogiques et conçoivent les schémas, comme leurs élèves le feront également, mais les enseignants doivent marquer les fragments de texte où leurs élèves trouveront les indices pour leur modélisation, et ainsi, révéler l'intention de conception du module.

- Notre formation expérimentale des enseignants a montré que les enseignants apprenaient à planifier et à conduire leurs cours, en adaptant consciemment le flux du travail en classe aux propres progrès des élèves, qu'ils pouvaient identifier selon les deux axes du contenu du module : le " technologique " et le "conceptuel."

Introduction

The problem of teachers’ own literacy is a challenging one, as students’ literacy, scientific in particular, tends to be limited to that of their teachers. The means of literacy transmission from teachers to students while the students are mostly reading special educational texts should be thoroughly investigated.

We explore, construct, and promote teachers’ instruments for teaching literacy to students and outline two major factors: the content of the texts themselves, and the teacher’s competencies needed to educate students. Our major question is: what should be the core of the teacher’s training?

The educational text is the main focus here: it contains the means of thinking to be assimilated by students, and at the same time it is the pedagogical instrument to be adopted by teachers. Consequently, the design of appropriate texts is studied widely as related to the conceptual change they aim to induce. Research within the conceptual change approach introduces refutation texts to support students’ transition from their previous everyday notions to scientific knowledge. Such texts refute various inappropriate ideas that students might have, which proves to be more productive than traditional expository texts (e.g., see Butterfuss & Kendeou, 2020; Dole & Sinatra, 1998; Murphy & Mason, 2006). The text may even be made incoherent on purpose, to prompt readers to make up for the incoherence themselves as they reconstruct the logical links that were deliberately skipped by the designers of the text (McNamara et al., 1996).

There is a trend today to construct a special type of educational text rather than adapt scientific texts for primary and early secondary school students. The difference is that the educational texts require active work from the learners, which will scaffold their acquisition of the concepts, while most common are expository texts, which thoroughly explain a topic, but are in a way self-sufficient and do not require work of the students other than reading. While we welcome the newer approach, we find it necessary to question not only the form but also the content of an educational text: the choice of the concepts delivered and the tasks that these texts ask students to solve.

The development of disciplinary literacy, which is often considered as related to general literacy, and the resulting increase of attention to modification of learning texts, demands changes in the way teachers are trained (Sutherland, 2008). A number of researchers (Gao et al., 2022; Grysko & Zygouris‐Coe, 2020; Lewis, Dema, & Harshbarger, 2014; Pearson, Moje, & Greenleaf, 2010; Wallace & Coffey, 2019) consider the integration between teaching general literacy and teaching science to be productive, especially in elementary school, where science activities may involve students in using language actively within a meaningful context, and thus help them develop their language skills and literacy in general (Akerson & Flanigan, 2000). Thus, pre-service teachers should at least become familiar with the idea that using science may leverage reading comprehension and vice versa. More active forms of teacher training may involve planning a lesson with a group of specialists, teaching it to students under supervision, and then discussing and modifying it (Cerbin & Kopp, 2006).

These tendencies are spreading worldwide: in modern Russian research literature, attention is also drawn towards the formation of scientific literacy (Korolev, 2020) and the integration of separate sciences into one natural science module (Rybalkina, 2018). Meanwhile, traditional teacher training focuses on the subject-related education of students and considers the particular technologies and methods to deliver special knowledge and skills that teachers are to assimilate (Bozko, 2020; Korolev, 2018; Melnikova, 2017). A new specialist type is introduced in current research, the trainer-technologist, whose job is to guide teachers as they plan the entire lesson process, including students’ learning activity, especially in the natural sciences (Trener-tekhnolog…, 2022).

Our major concern is to implement the Activity approach as an essential innovation in teacher training, which has already achieved promising results (Deyatel'nostnyy podkhod v obrazovanii, 2021). It is especially important to support teachers who are exploring the new methods and new educational content developed within this framework, as the Activity approach is highly demanding as compared with traditional learning: teachers have to organize students’ own inquiries instead of delivering them knowledge ready-made. A remarkable example of educational modules, developed on the basis of V.V. Davydov’s theory of developmental instruction (Davydov, 2008), is the “NartURE” introductory science course,” based on the “technological” framework of the emergence and development of scientific knowledge. It calls upon students (as well as their teachers) to dig into the new, rich “cultural” content (the history of technologies and crafts) and raises questions that the student will be answering in the scientific disciplines (biology, physics, and chemistry, as well as geometry, geography, and history) from a new, “cultural” point of view. Thus, our challenge was to train teachers to scaffold their students’ own inquiries during the lessons conducted with these learning materials and within the Activity approach to learning.

The ‘Twist’ of the NartURE Curriculum

The NartURE natural sciences’ module (Vysotskaya et al., 2020b; Yanishevskaya et al., 2021) was designed to introduce students to mankind’s transformations of natural materials and to the scientific interpretations of their terms and results. During this introduction, students will pose questions that their future special courses in biology, chemistry, or physics will be answering. The educational module scaffolds the development of learning situations, in which the origin of concepts of natural science within cultural human activity will be presented. Thus, the special “twist” of the course is as follows: How did man “teach” nature to work in his stead, while creating new cultural conditions for his own survival?

The origin of “scientific knowledge” belongs to the initial challenges that man faced, and which were solved once and for all. It was within arts and crafts that natural laws and phenomena came into consideration: the search for ways to handle natural materials and transform them to serve man’s needs was at the root of science. Students are asked to examine these initial problems and the technologies that were developed to solve them, before they proceed to learning special disciplines. Thus, man’s purposeful productive activity becomes the framework for acquisition of the basic concepts of the natural sciences, which delivers the cultural meaning of natural sciences. Students try out “natural science’s way of thinking,” while they learn to consider the matter through the “lens of mankind.”

This approach demands proper support for the learning task to be set by the students themselves and the organization of students’ discussions about the experiments they conducted or the models and schemas they devised. The appropriate learning materials include specially designed educational texts, which contain no ready-made solutions for the problems they pose. These texts serve for problematization (what is there to understand?), to provide samples of doing (what should be done to understand?) and thinking (how is it meant to be understood?). All the “storylines” of the textbook chapters (examples of text fragments will be presented below) follow these principles and purposes.

Three pillars of the NartURE module – the text, lab, and models – and the transitions between them are at the center of students’ work. This work starts with reading the text, the cornerstone of the whole module. Hands-on experiments are then conducted to recreate the ancient technologies (at least in part) described in the text, in order to fill in the gaps in description and to test the hypotheses that emerge through modeling of nature’s “work.” The models in turn demand repeated reference to the text and lab in order to test the models as means of prediction and explanation of how the technologies work.

This approach to introducing the natural sciences through testing ancient technologies requires changing the approach to teaching and new ways of training teachers. The training we organize is based on teachers’ adoption of two positions simultaneously: the position of a student and the position of the educational designer of this module.

Methods

Our research question concerns the ways that literacy in reading natural science texts can be passed from teachers to students, and through teacher training to teachers as a prerequisite. We investigate the possibility of this transmission, its possible terms and form. We strive to train the teachers to develop and correct a lesson promptly, adjusting it to the general goals of the educational module. It is essential that the teachers be provided with the means to design the lesson so as to promote evolving student–student and student–teacher inquiry-based communication and cooperation. Following Davydov’s approach, we assume that the new content of learning is vital here.

Teacher Training for NartURE

The general point of the NartURE module is for students to experience learning natural sciences in the context of their origin within man’s purposeful work, and applying the knowledge obtained to guide their own learning, inquiry-based and productive activity. The student is provided with the opportunity to take on the role of a “doer,” a “reformer of nature,” and to overcome the common misconceptions about reasons behind natural phenomena and about the contribution of scientific knowledge to solving everyday problems. Students learn to interpret transformations of natural materials and natural phenomena through models, diagrams, and schemas as means of theoretical thinking, and to explore the special role of the educational texts for the own work in the natural sciences. Consequently, the future teachers of this module have to adopt this approach (which is new for the majority of them) and bring it to life in their own teaching.

The teacher has to learn about the general ways that students progress through the module’s content: 1) analysis and interpretation of the texts; 2) reconstruction of the technologies and scientific experiments in a workshop and their comprehension; 3) the set of scientific concepts that reflect the results of the students’ own research through the special modeling.

We will now present an example of the teacher training setup: delivering basic concepts that are necessary for the “chemical” part of the integrated course.

A person has the appropriate chemical pre-concepts, if he or she can identify a substance’s transformation (from a hands-on probe, or from the text’s description) and model it with a schema (examples of transformations: limestone into lime, wood into charcoal, ore into metal). As students repeatedly read the text, they discover the substances that are necessary for the transformation (e.g., oxygen for burning, carbon dioxide to solidify slaked lime, coal to refine metal from ore) and they can provide reasons for the safety regulations when dealing with different substances.

The teacher looks up the corresponding text excerpts and discovers that in Chapters 5 and 6 (“Taming fire” and “Offense and defense”) they are: sustaining combustion and firefighting; safety regulations when dealing with flammable materials; combustion (burning) and charring as examples of transformations of substances; furnace and kiln constructions serving these purposes; application of combustible and non-combustible substances: coal, soot, char, natural gas, oxygen, carbon dioxide, carbohydrates, asbestos; firearms; Greek fire and gunpowder; burning coal and sulfur; fireworks safety regulations; metals implications; production of metals; mining industry; melting and smelting iron; cast iron and steel.

The content of NartURE revolves along two general lines – technological and conceptual – which refer to the general way that teachers work with the learning material (Obnovleniye soderzhaniya…, 2017). As they learn to teach, teachers focus on joining the conceptual and technological aspects of the content, which can be found in all course sections.

The technological line deals with the reconstruction of ancient technologies for making necessary items from raw materials (What is made of what with the help of what? And why is it done this way and not another?). From this point of view, the student begins to consider things and instruments in regard to the way they were obtained through man’s purposeful activity, and they note the goals and means chosen according to the requirements of the task. To clarify the operations, their meanings, and the role of various natural objects involved, a technological chart is drawn: a sequence of transformations that lead to desired results. The chart is the main instrument through which the educational text is interpreted, and it highlights the technological aspect.

It is crucial that the technological chart, as well as other interpretative schemas, be developed backwards, starting from the resulting product, which signifies the purpose of the human work, and the characteristics of which should thus suit man’s needs. Such an analysis of ancient and modern technologies, embedded mainly in the texts of the textbook, sets the general framework and instruments for students to consider an educational text in its functional aspects.

The conceptual line is the development of modeling to comprehend the transformations performed with the natural materials, transformations which correspond to the development of human concepts. The technological chart and other schemas, which scaffold transformation of the actions/operations with natural materials, are the means through which the contexts of techniques and technologies as well as the corresponding concepts are acquired. The schema’s content generally evolves from modeling operations that are needed to transform an object, through the lens of the required characteristics of the product and available characteristics of the material, towards modeling the object itself, which allows students to adopt the cultural ways of “seeing the invisible”: the representations of molecules, forces, heat, etc.

While the technological line of the module aims at the reconstruction of ancient technologies for making necessary objects from raw materials, it directly presents the content of each chapter (Table 1). It also sets the basis for the emergence of the main conceptual lines of the module, which deal with the ways people pass their knowledge from generation to generation. The entire conceptual line of the module presents the process of creation and development of means to comprehend how the technologies and natural phenomena work through models, and thereby scaffolds future transition to conventional systems of concepts in the natural sciences.

Table 1

NartURE’s table of contents

|

Chapter |

Contents |

|

1. How did people enable themselves to survive? |

Human basic needs and first activities to satisfy them. Animals and mankind. Settling over the planet. Hunting, gathering, farming, and cattle breeding. |

|

2. Edible or not? |

Making food. Bread, porridge. Wine, beer, vinegar. Kefir, cheese, curd, butter. Spice, salt, sugar, oil. Food preservation. |

|

3. From head to toe |

Making clothes and shoes. Simple clothes. Weaving and knitting. Materials for cloth-making. Making shoes: rubber and leather. Dyes. Soap. |

|

4. Building a house |

Building materials and simple mechanisms. Pulley and lever. Natural and artificial materials: clay, bricks, quicklime and slaked lime, chalk, limestone, marble, granite, sand, natron, glass, porcelain, cement, concrete. |

|

5. Taming fire |

Ways to build fire. Coal-making. Optics. Burning process and coal-making. Putting out fires. Asbestos. |

|

6. Offense and defense |

Means of war: building forts and creating weapons. Principles of fort building. Simple weapons. Bow. Gunpowder. Ballistics. Melting metals from ore. |

|

7. Fighting the unknown |

Medicine: treating wounds, curing illness, and preventing diseases. |

|

8. Finding the way home |

Things, that helped travelers to find their way. Navigation by constellation. Compass. Maps. Scale. Triangulation. Latitude and longitude. Transport. |

Note. Retrieved from Vysotskaya et al., 2017

The content as it is presented in the curriculum and in the textbook may be briefly presented as follows:

- “Taming fire”: identifying the components and products of combustion while considering ways to intensify or extinguish fire; oxygen as an indispensable “assistant of combustion”; charring: the differences in furnace construction for burning and for charring; the origin of charcoal and hard coal; the prediction of a substance’s combustibility;

- “Keeping gunpowder dry”: the purpose and the characteristics of gunpowder components;

- “The metal clangs”: the discovery of several different “missions” of coal in refining metals from ore – the heat source, “the transformation assistant,” and a component of cast iron and steel.

To plan and design a lesson, the teacher has to connect the plot lines, which organize the narration of the textbook and provide the text’s content, and the students’ actions, which support the text’s reading (lab work, model-building) and which comprise the basis for concept formation.

Design and Procedure

We have conducted three cycles of teacher training (12 participants in total) and followed the principles as outlined:

- associating text excerpts with the two general lines: the technological and conceptual;

- considering students’ work within the text–lab–model triad;

- trying out the student’s point of view in order to comprehend the intention of the curriculum design and thereby shaping the teacher’s own position.

Group discussions were audiotaped, and teachers’ notes, especially diagrams and schemas, were collected. Teachers’ questions and feedback during their own experience of conducting the NartURE curriculum were also collected afterwards. The data were then reviewed in their entirety. To illustrate teachers’ work with the curriculum content, we provide here excerpts from the sub-section on iron production: the text excerpt, teachers’ discussions and schemas, their insights and feedback.

Results

The excerpt from the sub-section on iron production describes the ancient technology of sponge-iron production (each sentence is numbered for reference):

Unlike metals, ore cannot be shaped by striking it, nor does it melt from heating (1). To produce copper, shattered chunks of the appropriate ore were mixed with a large amount of coal and heated in earthen pits or bloomeries (2). Part of this coal was burnt in order to provide the desired transformation – for this purpose, air was pumped into the furnace (3). The produced metal streams through grooves below and hardens in earthen molds (4).…

However, iron could not be smelted in the same way from iron ore (5). Bloomeries produced it as solid, porous pieces with coal and stone inclusions – a bloom, or sponge iron (6). To craft an item from iron, the bloom was forged: the incandescent piece was hammered (7). The excess coal was burnt out this way, and stone shards, which were stuck during smelting, were knocked out from the softened iron (8).…

Sometimes, in a big and well-heated furnace, the iron ore turned into pig iron or cast iron instead of wrought iron (9). The pig iron was cast into ingots, and it was liquefied when hammered instead of softening (10). The hardened pig iron is brittle and an item will break from a strong strike (11). At first it was considered defective and was cast (thrown) away (12).

The ability of pig iron to turn into stronger, malleable and springy steel was an outstanding discovery (13). This refining consists mainly of driving away most of the coal dissolved in molten pig iron (or crude iron) (14). (Vysotskaya et al., 2020a, pp. 26–27)

The students’ goal is to construct a technological chart for smelting iron from ore. A question in the text sets the task: “What is the difference between melting and smelting?” Another asks the student to agree or disagree with the idea that iron is contained in the ore, and it melts and flows out when the ore is heated. To answer these and many other questions, students have to design a technological chart, starting from the final product – iron, or an item made of iron – and proceed backwards to the raw material (ore) while answering three main questions: what is made of what and what is done to make it?

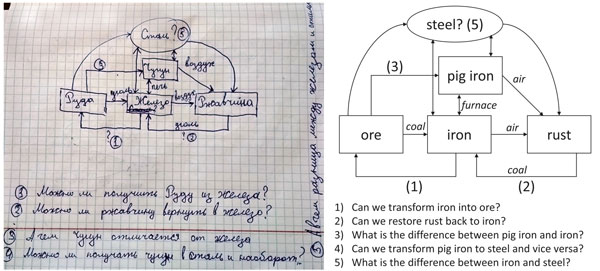

The teachers’ goal fits that of the students: they are to recreate the chart, while searching through the text for the knowledge they already have, but from the position of the “novice” students. Teachers mark the corresponding places in the text to connect each of them to the exact step in the technological chart (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A general chart connecting steel, pig iron, rust, iron, and ore – and the questions, marked with numbers, about transformations between the substances

According to the module’s general “cultural” idea, the final product is an item made of iron, which immediately poses questions about the desired characteristics of the item. A knife should be strong and flexible; a machine stand has to be huge, but cheap; some objects have to be shaped nicely, and others have to be quick and simple to make. Working with the text, students will find out that a knife has to be made from steel, that railings can be either cast or forged, that pig iron was first considered defective (text excerpt above, sentences 10–12), but was later used to mold cannon balls and gun carriages, columns, stands and rails, pots and pans, etc. Thus, students learn to find the connection between the item’s purpose and the material’s properties (structure–function relationships).

All the text excerpts that the teachers find are collected in order to put them onto the chart. The descriptions concern “doing and making things” and it is actions that are organized in the chart, whereas objects play a secondary role. The items here are considered according to their function: a product, a material, or an “assistant” for making things.

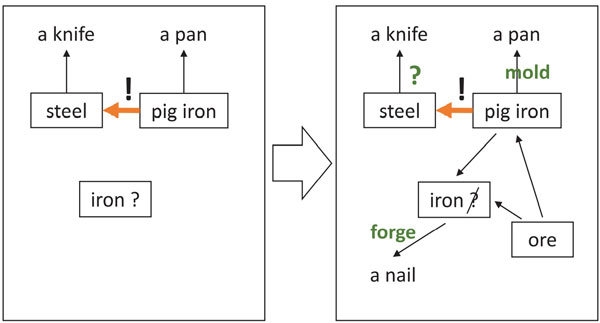

As our experimental teaching shows, both teachers and students tend to focus on nouns: objects, products, etc. They “fish out” from the text the “pig iron,” “sponge iron,” “wrought iron,” “steel,” but how are they related? Are they all alternative products? Or are they in a product–material relationship? At this point, most of the participant teachers failed to outline these relationships on the diagram (Figures 1, 2) The educational text, however, contains the clues, so the teachers have to both figure out the interrelations between the materials themselves and point out fragments that will allow students to answer the same questions in their classwork.

The actual work starts as human operations are extracted from the text and connected through the technological chart. For this purpose, the text is read over and over again: those things that were overlooked are now the most important, and the relationships are set anew (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Diagram’s progression (copied and translated by the authors from a teacher’s drawing)

Through working with the technological chart, the purpose of the natural scientific knowledge is revealed. The chart outlines a step-by-step prescription for people to follow. But there are always parts of procedures that require waiting: waiting while the ore and coal are burning in the bloomery; waiting for the pig iron to turn into steel in the open-hearth furnace; waiting till the charring clamp ceases to smoke, which means that the timber has turned into coal, etc. This is “nature’s” part of the work, not man’s – within the cultural procedure, this is the place allotted for natural phenomena. Thus, on a different level, from the “cultural” perspective, students (and their teachers) arrive at the functions of natural sciences: scientific concepts work where man leaves nature to do its part of the job, yet the entire procedure and the knowledge that guides it are cultural.

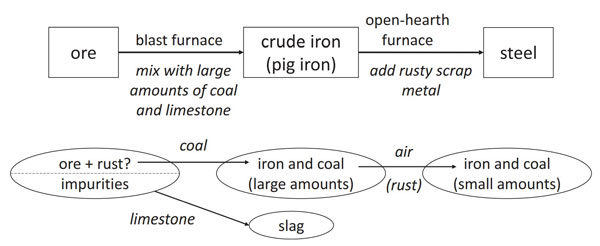

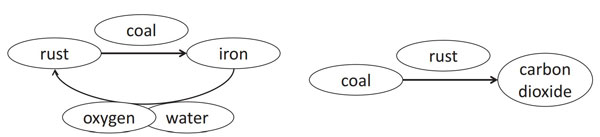

There are two episodes in steel production. The chemical conceptual line emerges here. Another layer has to be applied over the technological chart: labeling substances. It marks the substances’ transformations and sets subsequent questions and subsequent text revision: has the substance been changed? With the assistance of what other substance? Was the assisting substance used up or not?

The teachers came up with the technological chart, labeled the substances’ transformations, and marked text fragments (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The technological chart of steel production with the “substances layer” – teachers’ collective drawing, translated by the authors.

Figure 4. Advanced schemas of transformations, drawn by teachers, translated by the authors.

As teachers worked with the textbook, they revealed the conceptual lines behind the module and collected text fragments and assignments that scaffolded this or that concept formation. On the other hand, the teachers learned the role of each text fragment as related to its particular “technological” storyline. The result of the teacher training cycle was a “conceptual map” of the educational module, which was eventually enriched with the particular technological content laid along the transparent conceptual lines. Later on, these maps served teachers as their own means of macro- and micro-planning: teachers outlined the whole sequences of lessons beforehand, yet they could fluently adjust each lesson to the students’ progress in real time.

The lesson plans were transformed from straightforward scenarios into a map of learning materials following some general storyline, with a variety of laterals for students to explore. Mostly teachers focused on planning their own actions, relying on the students’ reactions as means of progress through the subject’s content (a kind of “signal” for teachers to provide the subsequent piece of information). Then the teachers’ approach changed: their lesson plans now present a variety of opportunities for students to explore the matter (with appropriate texts, supplementary lab works, additional materials), with the special way of modelling as the center, the goal, and the framework (Vysotskaya et al., 2017).

Thus, students are comparatively free in their own inquiry, and teachers scaffold their progress along the technological and conceptual lines, relying on the comprehension of the final result and their own experience as students. Two major functions of the teachers are thus outlined: 1) “sense-making” – keeping the tension of the “technological quest”: “what is made and how?” and 2) “modeling support” – asking, arguing, doubting, provoking students so they will have to refer to the modeling, which is the only way to sort out their misconceptions and to fill in the gaps in the technology descriptions. There are other missions for teachers: reminding students to reread the text, or preparing the workshop for students to test some simple parts of technologies – but the first two are the most important.

In general, our experience in teacher training showed promising results. All the teachers confessed that there was a lot for themselves to learn from the educational module. Plenty of facts that they previously knew, they never considered from the “technological” point of view – thus, they discovered new “practical” meanings of the knowledge they already had.

Discussion

The results of the teacher training series show that the Activity approach to teaching teachers is appropriate and productive. The cultural-historical framework allowed both designing new content for introducing natural sciences using the “technological” context, and changing the approach to teacher training towards more thoughtful lesson design.

Thus, we may deepen our comprehension of teachers’ possible ways to scaffold the formation of students’ disciplinary literacy, built through our previous studies (e.g., Vysotskaya & Yanishevskaya, 2021). The effects on teachers’ own literacy development, as one of the training results, are obvious.

However, the most essential part of the teachers’ competencies is comprehension of their students’ actions, which reveal the technological and conceptual content of each text fragment. Working within the text–lab–model triad, students reconstruct the general meanings of human cultural activities at the origin of knowledge of the natural sciences, which was the major objective of the NartURE curriculum. This revised context may comprise the actual basis for students’ text comprehension. Our research shows that a teacher’s work with the educational text is even more complicated than that of a student in the classroom. The teacher has to support students’ own reconstruction of the special meanings behind the text, without announcing them directly.

Conclusion

Shulman (1986) conducted a brilliant analysis of teachers’ qualification requirements at the end of the 19th and 20th centuries and concluded that the focus has drastically changed from sound disciplinary knowledge towards theoretical and practical pedagogical skills. We join his call for a balance between the two, and suggest the Activity-based approach to teacher training, which relies on learning materials designed within the developmental instruction framework. The results of our training cycles show that this approach is possible and provides changes in teachers’ attitudes towards lesson design and benefits teachers’ own disciplinary literacy as a byproduct.

Limitations

Further research is needed to develop the principles of our approach to teacher training in detail; now we have outlined only the general guidelines. Examples of the participants’ own lessons with their students as the result of their new competencies would also have been useful, but deserve a separate publication. We conclude that the approach described in this preliminary research is feasible and may support future studies in the domain of Activity-based teacher training.

Ethics Statement

Informed consent was obtained from participants before the experimental teacher training series.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Akerson, V. L., & Flanigan, J. (2000). Preparing preservice teachers to use an interdisciplinary approach to science and language arts instruction. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 11(4), 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009433221495

Bozhko N.N., Klevetova T.V., & Komissarova S.A. (2020). Proyektirovaniye professional'nykh situatsiy pri podgotovke budushchikh uchiteley fiziki i informatiki [Designing professional situations for future physics and informatics teacher training]. Sovremennye problemy nauki i obrazovaniya [Modern problems of science and education], 2. Retrieved from https://science-education.ru/ru/article/view?id=29651

Butterfuss, R., & Kendeou, P. (2020). Reducing interference from misconceptions: The role of inhibition in knowledge revision. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(4), 782. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000385

Cerbin, W., & Kopp, B. (2006). Lesson study as a model for building pedagogical knowledge and improving teaching. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 18(3), 250–257.

Davydov, V. V. (2008). Problems of developmental instruction: A theoretical and experimental psychological study. Nova Science Publishers, Incorporated. Retrieved from https://books.google.ru/books?id=r3YOAQAAMAAJ&hl=ru&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Dole, J.A., & Sinatra, G.M. (1998). Reconceptualizing change in the cognitive construction of knowledge. Educational Psychologist, 33(2–3), 109–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.1998.9653294

Gao, S., Hall, J.L., Zygouris-Coe, V., & Grysko, R.A. (2022). Understanding the role of science-specific literacy strategies in supporting science teaching and student learning. The Electronic Journal for Research in Science & Mathematics Education, 26(1), 33–55.

Grysko, R.A., & Zygouris‐Coe, V.V. I. (2020). Supporting disciplinary literacy and science learning in grades 3–5. The Reading Teacher, 73(4), 485–499. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1860

Korolev, M.Yu., & Odintsova, N.I. (2018). Podgotovka uchitelya yestestvoznaniya na osnove programm professional'noy perepodgotovki [Natural science teacher training based on professional training curricula], Fizika v shkole [Physics at school], S2, 19–24. Retrieved from https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=32577418

Korolev, M.Yu., & Petrova, E. B. (2020). Formirovaniye funktsional'noy gramotnosti i podgotovka uchitelya yestestvoznaniya i astronomii [Functional literacy formation and natural science and astronomy teacher training]. Fizika v shkole [Physics at school], S2, 12–17. https://doi.org/10.47639/0130-5522_2020_S2_12

Lewis, E., Dema, O., & Harshbarger, D. (2014). Preparation for practice: Elementary preservice teachers learning and using scientific classroom discourse community instructional strategies. School Science and Mathematics, 114(4), 154–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssm.12067

Lvovsky, V.A. (Ed.) (2021). Deyatel'nostnyy podkhod v obrazovanii. [Activity approach in education]. Book 4. Moscow, Non-profit partnership “Author's Club”. Retrieved from https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=47342345

McNamara, D.S., Kintsch, E., Songer, N.B., & Kintsch, W. (1996). Are good texts always better? Interactions of text coherence, background knowledge, and levels of understanding in learning from text. Cognition and Instruction, 14(1), 1–43. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci1401_1

Melnikova, G.F., Gilmanshina, S.I., & Sagitova R.N. (2017). Innovatsionnyy komponent podgotovki uchiteley v usloviyakh transformatsii yestestvennonauchnogo obrazovaniya (na primere uchiteley khimii) [Innovative component of teacher training in the context of the transformation of natural science education (the example of chemistry teachers)]. Sovremennye problemy nauki i obrazovaniya [Modern problems of science and education], 5. Retrieved from https://science-education.ru/ru/article/view?id=26854

Murphy, P. K., & Mason, L. (2006). Changing knowledge and beliefs. In P. A. Alexander & P. H. Winne (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 305–324). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Obnovleniye soderzhaniya osnovnogo obshchego obrazovaniya: Prirodovedeniye. [Updating the content of basic school education: Natural history] (2017). Non-profit partnership “Author's Club,” Moscow. Retrieved from http://author-club.org/shop/products/703/

Pearson, P.D., Moje, E., & Greenleaf, C. (2010). Literacy and science: Each in the service of the other. Science, 328(5977), 459–463. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1182595

Rybalkina, L.G. (2018). Predposylki formirovaniya mirovozzreniya uchitelya shkol'nogo predmeta "Yestestvoznaniye" [Prerequisites for the formation of the worldview of the natural science teacher]. Mir nauki. Pedagogika i Psikhologiya [World of Science. Pedagogy and psychology], 6(4), 27. Retrieved from https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/predposylki-formirovaniya-mirovozzreniya-uchitelya-shkolnogo-predm...

Shulman, L.S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X015002004

Sutherland, L.M. (2008). Reading in science: Developing high-quality student text and supporting effective teacher enactment. The Elementary School Journal, 109(2), 162–180. https://doi.org/10.1086/590524

Lvovsky, V.A. (Ed.) (2022). Trener-tekhnolog – novaya pedagogicheskaya pozitsiya [Trainer-technologist – a new pedagogical position]. Collection of materials of the IV Congress of trainer-technologists of activity educational practices. Non-profit partnership "Author's Club,” Moscow. Retrieved from https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=47493017

Vysotskaya, E., Khrebtova S., Lobanova, A., Rekhtman, I., & Yanishevskaya, M. (2017). Text–lab–model triad for testing ancient technologies: introductory science course for 5-graders. In EAPRIL2017 Conference Proceedings (pp. 294–309). Retrieved from https://www.eapril.org/sites/default/files/2018-04/ConfProceedings2017.pdf

Vysotskaya, E.V., Lobanova, A.D., Khrebtova, S.B., & Yanishevskaya M.A. (2020a). Prirodovedeniye, ili o chem rasskazhut yestestvennyye nauki. [Natural history, or what the natural sciences will discuss]. Book 6. Non-profit partnership "Author's Club,”, Moscow. Retrieved from http://author-club.org/shop/products/778/

Vysotskaya, E.V., Lobanova, A.D., Yanishevskaya, M.A., & Khrebtova, S.B. (2020b). Introduction to natural sciences: The human cultural history perspective. Psikhologicheskaya nauka i obrazovanie [Psychological science and education], 25(5), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.17759/pse.2020250508

Vysotskaya E.V., & Yanishevskaya, M.A. (2021). Problema formirovaniya funktsional'nogo otnosheniya k tekstu yestestvennonauchnogo soderzhaniya u vypusknikov nachal'noy shkoly. [The problem of forming a functional attitude to the natural science text among primary school graduates]. Chelovek v situatsii izmeneniy: realʹnyy i virtualʹnyy kontekst [The person in a situation of change: real and virtual context]. Materials of an international scientific conference. Moscow, pp. 292–295. Retrieved from https://www.rsuh.ru/upload/main/psy/conferences-and-seminars/2021/сборник%20на%20сайт.docx

Wallace, C.S., & Coffey, D.J. (2019). Investigating elementary preservice teachers’ designs for integrated science/literacy instruction highlighting similar cognitive processes. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 30(5), 507–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/1046560X.2019.1587569

Yanishevskaya, M., Vysotskaya, E., Lobanova, A., & Khrebtova, S. (2021). Activity-based introductory curriculum for mastering initial competencies: Natural sciences for urban students. In SHS Web of Conferences (Vol. 98). EDP Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20219803003