The Formation of Giftedness and Intelligence at School Age

Received: 05/15/2022

Accepted: 06/01/2022

DOI: 10.11621/nicep.2022.0205

To cite this article:

Joukova, E. S., Artemenkov, S. L., Bogoyavlenskaya, D. B. (2022). The Formation of Giftedness and Intelligence at School Age. New Ideas in Child and Educational Psychology, 2 (1-2), 80-92. DOI: 10.11621/nicep.2022.0205

Background. The problem of identifying and supporting gifted children is currently defined as one of the priority areas of science and education. It is important to understand that the generally accepted theoretical foundations of this field will define practice. Understanding giftedness as the ability to develop activities on one's own initiative (Bogoyavlenskaya, 1971) makes it possible to determine the role of intellect and motivation in this process. Through a longitudinal study, we have identified the development of these indicators throughout a child’s entire school years.

Objective. The purpose of this study was to trace the formation of giftedness during a child’s maturation in order to clarify its structure.

Design. Giftedness and intelligence level were measured at different ages. Giftedness was defined as the ability to develop activities on one's own initiative and measured by the "Creative Field" method (Bogoyavlenskaya, 1971, 2009). Intelligence was measured with the help of J. Raven's age-specific matrices: "Colored Progressive Matrices" and "Standard Progressive Matrices." The study involved 60 children in the 2nd grade, 53 children in the 4th grade, 42 children in the 6th grade, and 34 children in the 9th grade. Mathematical analysis was carried out on the final sample of 34 children.

Results. The formation of giftedness and intelligence during the school period was identified using a model of latent linear changes. Giftedness showed stability and growth from grades 2 to 9. The intelligence indicators for the group varied with age, showing an increase in the variety of values, along with a decrease in their average value.

Conclusion. The discrepancy between the lines of development of giftedness and those of intelligence proved the illegitimacy of reducing giftedness to the level of intelligence. Giftedness is based on a person’s leading cognitive motivation, which is itself based on the level of intelligence necessary for mastering the activity. Preserving the dominance of cognitive motivation in activities throughout the child’s development ultimately affects the growth of intelligence. This article discusses current approaches to working with gifted children and points out the need to change the focus to less formalized methods, with more emphasis on the development of the child's personality.

Highlights- A longitudinal study made it possible to identify, in a linear approximation, the characteristic signs of the development of giftedness and intelligence of children throughout school age. The discrepancy between the lines of development of giftedness and those of intelligence on average for the group showed the fallacy of reducing giftedness to intelligence only.

- Throughout all stages of development, we saw a gradual unfolding of the children’s ability to develop activities on their own initiative, which is explained by the personal characteristics inherent in this group. Their creative activity sprang from the individual’s cognitive orientation.

- Our heuristic group of children was distinguished by the growth and preservation of intelligence throughout adulthood. We think that it is the dominance of cognitive motivation in activity during the child’s maturation that ultimately affects the growth of his or her intelligence.

- A certain decline in the average value of intellectual assessments in the group and their fan character indicated the possible diversity of intellectual abilities, as well as the maturation of the children and their conscious self-determination.

- The data we obtained indicated the need to shift the emphasis of work with gifted children from the complexity of programs, toward greater attention to the development of personality. The organization of "live" non-formalized interaction with the teacher on topics of interest to the child can help in the formation of an active personality.

Актуальность. Проблема выявления и поддержки одаренных детей в настоящее время определяется как одно из приоритетных направлений науки и образования. Важно понимать, что принятые в качестве генеральных теоретические основания будут реализованы в практике. Понимание одаренности как способности к развитию деятельности по собственной инициативе (Богоявленская, 1971) позволяет определить роль интеллекта и мотивации в этом процессе. Посредством лонгитюдного исследования нами выявляется развитие этих показателей на протяжении всего школьного периода развития ребенка.

Цель. Целью данного исследования было проследить становление одаренности на протяжении взросления ребенка для уточнения ее структуры.

Дизайн. На разных возрастных этапах были исследованы одаренность и уровень интеллекта. Одаренность исследовалась как способность к развитию деятельности по собственной инициативе методом «Креативное поле» (Богоявленская, 1971, 2009). Интеллект исследовался с помощью возрастных вариантов матриц Дж. Равена: «Цветные прогрессивные матрицы» и «Стандартные прогрессивные матрицы». В исследовании приняли участие во 2 классе – 60 детей, в 4 классе – 53 человека, в 6 классе – 42 человека и в 9 классе – 34 человека. Математический анализ проводился на выборке из 34 человек.

Результаты. Становление одаренности и интеллекта на протяжении школьного периода характеризуется с помощью модели латентных линейных изменений. Одаренность демонстрирует стабильность и рост на протяжении от 2 к 9 классам. Показатели интеллекта по группе с возрастом обнаруживают как некоторое снижение, так и рост с увеличением разнообразия оценок при уменьшении среднего значения.

Вывод. Несовпадение линий развития одаренности и интеллекта доказывает неправомерность сведения одаренности к уровню интеллекта. Одаренность имеет в своей основе ведущую познавательную мотивацию, которая опирается на необходимый для овладения деятельностью уровень интеллекта. Сохранение доминирования познавательной мотивации в деятельности на протяжении взросления ребенка в конечном счете оказывает влияние на рост интеллекта. В статье обсуждаются современные подходы к работе с одаренными детьми и указывается на необходимость смены ее акцентов на менее формализованные и более ориентированные на развитие личности ребенка.

Ключевые положения- Лонгитюдное исследование позволило выявить в линейном приближении характерные признаки развития одаренности и интеллекта детей на протяжении школьного возраста. Несовпадение линий развития одаренности и интеллекта в среднем по группе позволяет не сводить одаренность только к интеллекту.

- На протяжении всех срезов мы видим постепенное раскрытие способности к развитию деятельности по собственной инициативе, что объясняется личностными особенностями, присущими этой группе. Её активность рождается из познавательной направленности личности.

- Эвристическая группа детей отличается ростом и сохранением интеллекта на протяжении взросления. По нашим представлениям, именно доминирование познавательной мотивации в деятельности на протяжении взросления ребенка, в конечном счете, оказывает влияние на рост интеллекта.

- Некоторый спад среднего значения интеллектуального развития по группе и его веерный характер говорит о возможном многообразии интеллектуальных способностей, а также о взрослении детей, их осознанном самоопределении.

- Полученные данные говорят о необходимости смещения акцентов в работе с одаренными детьми с усложнения программ в сторону большего внимания к становлению личности. Организация «живого» неформализованного взаимодействия с педагогом на интересующие ребенка темы может помочь в формировании активной личности.

Introducción. El problema de identificar y apoyar a los niños superdotados se define actualmente como una de las áreas prioritarias de la ciencia y educación. Es importante entender que los fundamentos teóricos aceptados como generales serán implementados en la práctica. Entender la superdotación como la capacidad de desarrollar actividades por iniciativa propia (Bogoyavlenskaya, 1971) permite determinar el papel del intelecto y la motivación en este proceso. A través de un estudio longitudinal revelamos el desarrollo de estos indicadores a lo largo de todo el período escolar del desarrollo del niño.

Objetivo. El propósito del presente estudio fue rastrear la formación de superdotación durante el crecimiento de un niño para aclarar su estructura.

Diseño. La superdotación y el nivel de la inteligencia se estudiaron en diferentes etapas de edad. La superdotación se evaluó como la capacidad para desarrollar actividades por iniciativa propia utilizando el método del "Campo Creativo" (Bogoyavlenskaya, 1971, 2009). La inteligencia se estudió con la ayuda de las matrices específicas por edad de J. Raven: "Matrices progresivas coloreadas" y "Matrices progresivas estándar". El estudio involucró a 60 niños del segundo grado, 53 niños del cuarto grado, 42 niños del sexto grado y 34 niños del noveno grado. El análisis matemático se realizó sobre una muestra de 34 personas.

Resultados. Se caracteriza la formación de la superdotación y la inteligencia durante el período escolar mediante un modelo de cambios lineales latentes. La superdotación muestra estabilidad y crecimiento del segundo a noveno grado. Los indicadores de inteligencia para el grupo con tiempo muestran tanto una ligera disminución como un aumento con el aumento en la variedad de estimaciones con la disminución en el valor promedio.

Conclusión. La discrepancia entre las líneas de desarrollo de superdotación e inteligencia demuestra la ilegitimidad de reducir la superdotación al nivel de la inteligencia. La superdotación se basa en la motivación cognitiva principal, que se basa en el nivel de inteligencia necesario para dominar la actividad. La preservación del dominio de la motivación cognitiva en las actividades a lo largo del crecimiento del niño afecta en última instancia al crecimiento de la inteligencia. El artículo analiza los enfoques modernos para trabajar con niños superdotados y señala la necesidad de cambiar su enfoque a menos formalizado y más centrado en el desarrollo de la personalidad del niño.

Destacados- El estudio longitudinal permitió identificar, en una aproximación lineal, los rasgos característicos del desarrollo de superdotación y la inteligencia de los niños a lo largo de la edad escolar.

- La discrepancia entre las líneas del desarrollo de superdotación e inteligencia para el grupo en promedio permite no reducir la superdotación a la inteligencia solamente.

- A lo largo de todos los apartados se observa una paulatina revelación de la capacidad de desarrollar actividades por iniciativa propia, lo que se explica por las características personales inherentes a este colectivo. Su actividad nace de la orientación cognitiva del individuo.

- El grupo heurístico de los niños se distingue por el crecimiento y conservación de la inteligencia a lo largo de la edad adulta. De acuerdo con nuestras ideas, es el predominio de la motivación cognitiva en la actividad durante el crecimiento del niño lo que finalmente afecta al crecimiento de inteligencia.

- Una cierta disminución en el valor promedio del desarrollo intelectual en el grupo y su carácter indica la posible diversidad de habilidades intelectuales, así como la maduración de los niños, su autodeterminación consciente.

- Los datos obtenidos indican la necesidad de desplazar el énfasis en el trabajo con superdotados desde la complejidad de los programas hacia una mayor atención al desarrollo de la personalidad. La organización de una interacción no formalizada "en vivo" con el maestro sobre temas de interés para el niño puede ayudar a la formación de una personalidad activa.

Origines. Le problème de l`identification et du soutien des enfants talentueux est défini comme l`un des domaines prioritaires de la science et de l`éducation. Il est important de comprendre que le fondement théorétique accepté comme général sera mis en pratique. Comprendre la douance comme la capacité à développer des activités de sa propre initiative (Diana B. Bogoyavlenskaya, 1971) permet de déterminer le rôle de l'intellect et de la motivation dans ce processus. Par une étude de longue durée, nous révélons l'évolution de ces indicateurs tout au long de la période scolaire du développement d'un enfant.

Objectif. L`objectif de cette étude était de retracer la formation de la douance au cours de la croissance d'un enfant afin de clarifier sa structure.

Conception. La douance et le niveau d'intelligence ont été étudiés à différentes étapes d'âge. La douance a été étudiée comme la capacité à développer des activités de sa propre initiative en utilisant la méthode "Champ créatif" (Diana B. Bogoyavlenskaya, 1971, 2009). L'intelligence a été étudiée à l'aide des matrices progressives par âge de J. Raven : " Matrices Progressives Colorées " et " Matrices Progressives Standard ". L'étude a porté sur 60 enfants de 2e année, 53 enfants de 4e année, 42 enfants de 6e année et 34 enfants de 9e année. L'analyse mathématique a été effectuée sur un échantillon de 34 personnes.

Résultats. La formation de la douance et de l'intelligence pendant la période scolaire est caractérisée à l'aide d'un modèle de changements linéaires latents. La douance montre une stabilité et une croissance de la 2e à la 9e année. Les indicateurs d'intelligence pour le groupe avec l'âge montrent à la fois une légère diminution et une augmentation avec une augmentation de la variété des estimations avec une diminution de la valeur moyenne.

Conclusion. Le décalage entre les lignes de développement de la douance et de l'intelligence prouve l'inconsistance de la réduction de la douance au niveau de l'intelligence. La douance repose sur la motivation cognitive dominante, qui repose sur le niveau d'intelligence nécessaire à la maîtrise de l'activité. La préservation de la prédominance de la motivation cognitive dans les activités tout au long de la croissance de l'enfant affecte finalement la croissance de l'intelligence. L'article discute des approches modernes du travail avec les enfants surdoués et souligne la nécessité de changer son orientation vers une approche moins formalisée et plus axée sur le développement de la personnalité de l'enfant.

Points principaux- Une étude longitudinale a permis d'identifier, dans une approximation linéaire, les signes caractéristiques du développement de la douance et de l'intelligence des enfants tout au long de l'âge scolaire.

- Le décalage entre les lignes de développement de la douance et de l'intelligence en moyenne pour le groupe permet de ne pas réduire la douance à la seule intelligence.

- Dans toutes les sections, on constate une divulgation graduelle de la capacité à développer des activités de sa propre initiative, ce qui s'explique par les caractéristiques personnelles inhérentes à ce groupe. Son activité naît de l'orientation cognitive de l'individu.

- Le groupe heuristique des enfants se distingue par la croissance et la préservation de l'intelligence tout au long de l'âge adulte. Selon nos idées, c'est la prédominance de la motivation cognitive dans l'activité pendant la croissance d'un enfant qui affecte finalement la croissance de l'intelligence.

- Une certaine baisse de la valeur moyenne du développement intellectuel dans le groupe et son caractère fan indique la possible diversité des capacités intellectuelles, ainsi que la maturation des enfants, leur autodétermination consciente.

- Les données obtenues indiquent la nécessité de déplacer l'accent dans le travail avec les enfants surdoués de la complexité des programmes vers une plus grande attention au développement de la personnalité. L'organisation d'interactions non formalisées "en direct" avec l'enseignant sur des sujets d'intérêt pour l'enfant peut aider à la formation d'une personnalité active.

Introduction

Diagnosis of giftedness in childhood requires verification throughout the child’s course of maturation. A high level of intelligence at school, which is often understood as the main indicator of giftedness, does not always result in the further realization of a child’s abilities. A biographical analysis based on surveys of scientists and artists who demonstrated a high level of achievement allows us to highlight the qualities that characterized them as they developed. It is notable that a high level of intelligence was not a key indicator, but rather a high level of interest in the chosen field of activity. Mastering knowledge in a subject of interest is in the nature of “discovery for oneself:” testing hypotheses and independently reaching an already perfected discovery. For example, the "inventing the wheel" is a natural and necessary result of a full-fledged interest, since it provides a new quality of knowledge appropriation.

The development of the study of giftedness has a long history and is currently characterized by combining the characteristics identified in creative individuals through different research concepts. According to one of the leading researchers on creativity, Todd Lubart (Lubart et al., 2009), creativity is the result of the convergence of cognitive, conative (habitual ways of behaving: personality traits, cognitive styles, and motivation), and environmental factors. But the sum of these factors does not define the whole.

Currently, researchers are actively exploring differences in the processes involved in obtaining solutions to creative and non-creative tasks. They are raising the question of the metacognitive functions that govern the choice of subprocesses and their recurrent use (Lubart et al., 2009, p. 116). Independently, the physiological component is being studied using the methods of modern medical diagnostics (EEG). The results obtained fill out the picture of the diversity of creativity, but do not answer the main question of what determines the formation of giftedness. Western science has not yet succeeded in determining the main cause of the development of giftedness, its "supporting structure," and what simply accompanies this complex process.

The Russian concept of creativity (Bogoyavlenskaya, 2009) has already answered these questions. It defines these metacognitive functions as interest in activities and the dominance of cognitive motivation. This concept involves no external stimulation for the creator, thus raising questions about the study of creativity in a new way.

In Russian psychology, the framework established by the schools of L.S. Vygotsky (1983), S.L. Rubinshtein (1922), and B.M. Teplov (1985) has for many years understood giftedness as the ability to develop activities on one's own initiative (Bogoyavlenskaya, 2009; Bogoyavlenskaya, Joukova, & Artemenkov, 2021). This ability is embodied in a unit that combines the individual’s intellectual and motivational components. The “Creative Field” method (Bogoyavlenskaya, 2009) makes it possible to identify cognitive motivation, which ensures that the creative individual goes beyond the requirements of the tasks presented: he or she starts with finding ways to solve problems, then discovering new laws, and finally poses a theoretical solution itself.

In previous studies using the “Creative Field” method, the experiments identified three groups that differ significantly in the form and essence of the activities performed (Bogoyavlenskaya, 2009). The first, called the stimulus-productive group, successfully finds a way to solve the problem and uses it as an algorithm in the system of tasks, demonstrating effectiveness within the framework of the presented stimulus. The second, the so-called heuristic group, not only successfully copes with the task, but, on its own initiative, moves further in knowledge and discovers new lawfulness in the system of tasks. This achievement characterizes this group as gifted. The third group, represented by those who reach the level of constructing a theory, is not typical for elementary school-age children (it was observed in a single case).

Methods

We began a longitudinal study of giftedness using the Creative Field method in 2013; it continues to the present.

Participants

The first longitudinal slice was carried out on 60 2nd grade students at a school in Moscow. Further testing was carried out in 4th, 6th, and 9th grades. The sample was reduced naturally and by the 9th grade the group consisted of 34 respondents. The last testing was carried out in the 9th grade, because at this time students generally have greater maturity and awareness of their actions, due to scheduled exams and possible changes in studies (transition to 10th grade, college admission).

Procedure

Giftedness was assessed by the "Creative Field" method (Bogoyavlenskaya, 1971, 2009) which was carried out in methods appropriate to the age of the subjects: in the 2nd and 4th grades - "Animals in the Circus;" in the 6th and 9th grades -- "Sea Battle" (planar modification of the original spatial method). We traditionally compared our understanding of giftedness with the understanding of giftedness as a high level of intelligence, due to the dominant position of the latter in current approaches to research in foreign and domestic science. The level of intellectual development was measured using the tests of J. Raven called “Colored Progressive Matrices” and “Standard Progressive Matrices.”

Results

The variables of the longitudinal study are presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1

Designations of the measured variables

|

|

Measured variables |

|||

|

2nd grade |

4th grade |

6th grade |

9th grade |

|

|

Giftedness |

A2 |

A4 |

A6 |

A9 |

|

Intelligence |

R2 |

R4 |

R6 |

R9 |

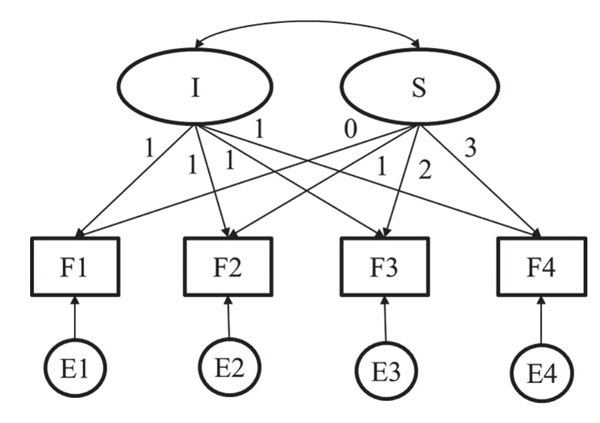

Mathematical analysis was carried out using the method of modeling latent linear changes, which is most often used to analyze repeat measurements of data obtained in the course of longitudinal studies (Mitina, & Barabanschikov, 2008). A block diagram that reflects the linear change in the values of latent factors throughout a child’s schooling is shown in Figure 1.

Two separate models of latent linear changes in giftedness and intelligence were obtained by replacing the factors F in the model in Figure 1 with each of the model latent factors A and R. Thus, the indicators E1, E2, E3, and E4 in both cases will indicate the variables measured in the longitudinal study (A2, A4, A6, A9 or R2, R4, R6, R9). Factor loading I was assumed to be the same for all four longitudinal slices, and changes by one S with each step to the next slice. Thus, factor I corresponded to a constant, and factor S corresponded to the slope of the growth line of the latent factor (taking into account the possibility of it both increasing and decreasing).

Figure 1. Block diagram of the latent linear growth model for 4 longitudinal slices

Calculations and plotting were carried out in the lavaan and ggplot2 packages of the R programming language.

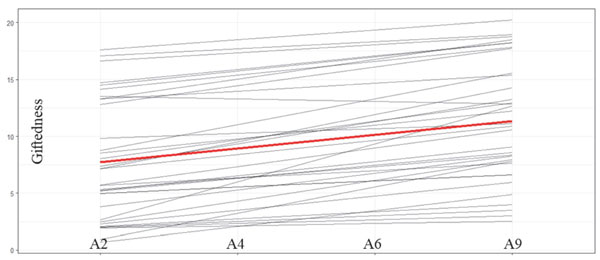

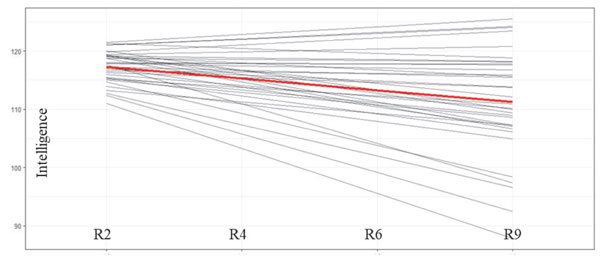

An analysis of the results of a longitudinal study showed that the factors of giftedness, which reflects the ability to develop activities on one's own initiative, and intelligence, in general, developed differently. The corresponding graphs of latent changes in giftedness and intelligence are shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2. The general graph of changes in giftedness for 34 subjects (red color shows the change in the average value)

Figure 3. The general graph of changes in intelligence for 34 subjects (red color shows the change in the average value)

From the graphs in Figures 2 and 3, we can see that with age, the ability to develop activities at the initiative of the subject (giftedness) increased on average, while the level of intellectual development decreased on average, probably due to the growth of school requirements. In addition to the change in average indicators, it can be seen that the development of intelligence had more of a fan character, which means a movement from a smaller variety of estimates to a greater variety – to both their increase and decrease. A large scatter of data indicates that with age, the children showed greater individualization and differentiation, which is explained by their maturation, the growth of self-awareness, and development as a student. For giftedness, we saw a more gradual development with a trend towards an overall increase in grades. Giftedness increased in all subjects except one, in whom it slightly decreased.

The results we obtained allow us to confirm the thesis about the impossibility of reducing giftedness to the development of intelligence (Joukova, Artemenkov, & Bogoyavlenskaya, 2019; Bogoyavlenskaya, Artemenkov, & Joukova, 2021). Giftedness is a special personality structure, where the intellect acts through the prism of the leading cognitive motive.

Discussion

In earlier published material (Artemenkov, Bogoyavlenskaya, & Joukova, 2021; Bogoyavlenskaya, Joukova, 2021), we showed how, over three periods (grades 2-4-6), intelligence develops in a heuristic group of subjects. Children in the heuristic group maintained and increased their levels of intelligence, while the stimulus-productive group demonstrated either the preservation or decrease in the level of intelligence. We emphasize that we are talking about children with a high level of intelligence. Children experiencing difficulties in mastering activities in the learning experiment did not fall into this group.

The main difference between the heuristic and stimulus-productive groups was not so much their intelligence (it can be equal in both groups), but motivation. Internal acceptance of the task does not allow heurists to perform it formally. Cognitive motivation is the "locomotive" that provides access to new levels of knowledge (heuristics). And maintenance and increase in the values of intelligence indicators are perfectly explained by the express interest and leading cognitive motivation shown in the activities of this group of children.

Our results allow us to take a broader look at the logic of the development of the theory of giftedness, which is limited by the scope of research opportunities. The modern logic behind the method of studying giftedness in psychology is quite understandable. The ability to test the field of intellect is the most developed, while the problem of motivation is much more difficult to measure. Studying motives with the help of questionnaires and self-reports not only invites random error, but also a conscious distortion. Because of this, reliance on questionnaires in assessing motivation seems to be of little use. The "Creative field" method allows you to situate the cognitive motivation in the activity.

In our opinion, the result of this study is extremely important. It established the leading role of cognitive motivation in the development of giftedness and, ultimately, intelligence, which has significant implications for different pedagogical interventions. The development of the intellect is obligatory and necessary, but within the pedagogical process, emphasis should be placed differently. At present, the definition of giftedness as a high level of intelligence underlies the features of curricula for the development of gifted children, the main characteristic of which is an increase in the level of complexity and volume of educational material, which leads to overwhelming workloads and a loss of interest in learning already in high school. The dominance of eclecticism in ideas about the nature of giftedness and creativity leads in modern science to an attempt to equip the child with allegedly effective ways to discover something new.

From our point of view, the mandate “to discover something new” is harmful and destructive, because it is divorced from psychic reality and directs the individual only at an external product. As a result, a person in the 21st century is urged to create not in order to unravel the secrets of nature and to understand his place in it, but to come up with something “original.” And although there is some play on words here, since any discovery is necessarily distinguished by novelty -- that is, originality -- this reflects increased attention to the process of making, the emergence of manufacturability and the mechanistic idea that “I will now learn to create and be creative.” By defining a particular characteristic as a goal, we deprive the idea of its meaning.

In reality, the development of a scientific idea, industry, etc. occurs only after many hours and years of attention to a problem, reflection on this topic, practice, and mistakes while living this topic; only then does the gestalt change, to use the language of the beginning of the last century. The new idea is revealed to a thinking person. This is exactly how science progresses and the creator’s personal development takes place in it. An analysis of individual elements of a creative act with the aim of getting insight into how to reproduce them not only misleads an entire generation, but has the opposite effect: it hinders the development of thought and science as its derivative.

The phenomenon of children achieving highly creative results already in their youth is interesting. Very often we see the completion of creative achievements starting at a very young age. But even such manifest talent does not ensure its further fruitful realization. This leads to the idea that the formation of a particular personality characteristic (intelligence, abilities, emotional-volitional, regulatory sphere) is not sufficient for creativity; it is necessary to mature the direction of the personality, so that all its aspects will work toward one’s "life's work."

Pedagogy plays a key role in resolving this issue. It seems to us that live contact on topics that interest the child and interaction with the teacher on the logic of the movement of his thoughts, would help the child in the formation of giftedness, enrichment, and developing his interests. The pedagogical model capable of achieving this took place in the work of teachers of the old school, when the teacher was recognized as the bearer of culture, and education was not yet so formalized and did not belong to the service sector. Excessive control and formalism do not contribute to the emergence of live communication and the manifestation of creativity at school.

The idea that a gifted child needs a different co-creative model of communication with a teacher perhaps does not get adopted for formal reasons, like the difficulties of fixing and controlling the work of a teacher, measuring the result of an activity, etc. On the other hand, the question arises of the psychological readiness of the pedagogical community for this work. But, despite all the difficulties that arise, it is necessary to organize such an approach at school, as is being successfully carried out, for example, within the framework of the Step into the Future Science Youth Forum (http://www.step-into-the-future.ru).

Conclusion

Based on the data from an experimental longitudinal study of giftedness and intelligence of schoolchildren in grades 2-9, modeling of latent linear changes for giftedness and intelligence was carried out. The results were as follows:

- With age, schoolchildren’s ability to develop activities on their own initiative increased on average, while the level of their intellectual development decreased on average.

- The development of giftedness as a whole was progressive without expanding the range of grades, while the development of intelligence was characterized by an expansion of differentiation in the form of a fan.

- Our results allow us to confirm the thesis that it is impossible to reduce giftedness to the development of intelligence (Joukova et al., 2019; Bogoyavlenskaya, Artemenkov, & Joukova, 2021). This is explained by the fact that giftedness is a special personality structure, whereas the intellect acts through the prism of the person’s leading cognitive motive.

- The leading role of cognitive motivation in the development of giftedness and ultimately intellect, implies the need for significantly different pedagogical interventions than are used today. A gifted child needs a different co-creative model of communication with a teacher.

Limitations

For greater validity of the conclusions, it is desirable to expand the sample through research within different educational institutions, which will confirm the data obtained and exclude the influence of the social component. This will allow a deeper analysis of the development of giftedness and intelligence at school age.

Ethics Statement

Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the parents of all children.

Author Contributions

Research and experiments were carried out by E.S. Joukova. S.L. Artemenkov conducted a mathematical analysis of the data. Dr. D.B. Bogoyavlenskaya developed the theoretical and practical basis for the study: a method, scales, and techniques for experimental diagnosis of giftedness in children of different ages. The authors jointly discussed the results of the research and collaborated on the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to all parents, teachers and children; to their colleagues from Psychological Institute of Russian Academy of Education (PI RAE) and Moscow State University of Psychology & Education (MSUPE): and the staff of school No. 1679 in Moscow, who helped in this work.

References

-

Artemenkov, S.L., Bogoyavlenskaya, D.B., & Joukova, E.S. (2021). Intellektualʹʹnaia i motivatsionnaia komponenty v longitiudnom issledovanii odarennosti [Intellectual and motivational components in the longitudinal study of giftedness]. Problemy Sovremennogo Oobrazovaniia [Problems of Modern Education], 1, 47-61. https://doi.org/10.31862/2218-8711-2021-1-47-61

-

Bogoyavlenskaya, D.B. (1971). Metod issledovaniia urovnei intellektual'noi aktivnosti [The method of studying the level of intellectual activity]. Voprosy Psikhologii [Issues of Psychology], 1, 144-146.

-

Bogoyavlenskaya, D.B. (2009). Psikhologiia tvorcheskikh sposobnostei [Psychology of creative abilities]. Samara: Fedorov.

-

Bogoyavlenskaya, D.B., Artemenkov, S.L., & Joukova, E.S. (2021). Longitiudnoe issledovanie razvitiia odarennosti [Longitudinal Study on the Development of Giftedness]. Eksperimental'naia psikhologia [Experimental Psychology], 14(3), 122–137. https://doi.org/10.17759/exppsy.2021140309

-

Bogoyavlenskaya, D.B., Joukova, E.S., & Artemenkov, S.L. (2021). K Iubileiu B.M. Teplova: evoliutsiia poniatiia odarennosti [To the anniversary of B.M. Teplov: the evolution of the understanding of giftedness]. In M.K. Kabardov, Iu.P. Zinchenko, & A.K. Osnitskii (Eds.), Mezhdunarodnaia konferentsiia, posviashchennaia 125-letiiu so dnia rozhdeniia B.M. Teplova "Differentsial'naia psikhologiia i psikhofiziologiia segodnia: sposobnosti, obrazovanie, professionalizm" [International conference dedicated to the 125th anniversary of the birth of B.M. Teplov "Various psychology and psychophysiology today: opportunities, education, professionalism"] (pp. 103-108). Moscow, PI RAO.

-

Bogoyavlenskaya, D.B., & Joukova, E.S. (2021). Rol' motivatsii v razvitii kognitivnykh sposobnostei [The role of motivation in the development of cognitive abilities]. In Pervyi natsional'nyi kongress po kognitivnym issledovaniiam, iskusstvennomu intellektu i neiroinformatike. IX mezhdunarodnaia konferentsiia po kognitivnoi nauke. Sbornik nauchnykh trudov [The First National Congress on Cognitive Research of Artificial Intelligence and Neuroinformatics. IX International Conference on Cognitive Science. Collection of scientific papers] (pp. 399-402). Moscow.

-

Vygotsky, L.S. (1983). Sobranie sochinenii v 6-ti t. T.5 Osnovy defektologii [Collected works in 6 vols. Vol. 5 Fundamentals of defectology]. Moscow, Pedagogika.

-

Joukova, E.S., Artemenkov, S.L., & Bogoyavlenskaya, D.B., (2019). Issledovanie intellektual'noi aktivnosti v mladshem shkol'nom i podrostkovom vozraste [Research of intellectual activity in primary school and adolescence]. Modelirovanie i Analiz Dannykh [Data Modeling and Analysis], 1, 11-29.

-

Lubart, T., Mouchiroud, C., Tordjman, S., & Zenasni, F. (2009). Psikhologiia kreativnosti [Psychology of Ccreativity]. Moscow, Kogito-Tsentr.

-

Mitina, O.V., & Barabanschikov, V.A. (2008). Strukturnye uravneniia dlia modelirovaniia skrytykh krivykh [Structural Equations for Latent Curve Modeling]. Eksperimental'naia psikhologia [Experimental Psychology], 1(1), 131–148.

-

Rubinshtein, S.L. (1922). Printsip tvorcheskoi samodeiatel'nosti [The principle of creative self-activity]. In Uchenye zapiski vysshei shkoly g. Odessy. T. 2. [Scientific notes of the higher school of Odessa. Vol. 2]

-

Teplov, B.M. (1985). Psikhologiia muzykal'nykh sposobnostei. Izbrannye trudy. V 2 tomakh. T.1. [Psychology of musical abilities. Selected works. In 2 volumes. Vol. 1]. Moscow, Pedagogika.