Features of Imagination in 5-6-Year-Old Children

Received: 09/14/2023

Accepted: 11/24/2023

DOI: 10.11621/nicep.2023.0505

To cite this article:

Almazova, O. V. , Bukhalenkova, D. A., Chichinina, E.A. (2023). Features of Imagination in 5-6-Year-Old Children. New Ideas in Child and Educational Psychology, 3 (3-4), 82-100. DOI: 10.11621/nicep.2023.0505

Background. The relevance of this study is due, on the one hand, to the importance of imagination for children’s cognitive and emotional development, and on the other hand, to the contradictory results of modern research on the development of the imagination of senior preschoolers.

Objective. The aim of the study was to evaluate and identify the Types of productive imagination in pupils of the senior kindergarten groups.

Design. To assess the children’s imagination, the technique of “Complete the Figure” was used (Dyachenko, 2007). The preschoolers’ drawings were analyzed in terms of flexibility, elaboration, and originality. The study participants were 768 pupils of senior kindergarten groups from four regions of Russia (Moscow, the Republics of Sakha and Tatarstan, and the Perm Territory); they ranged from 58 to 72 months of age (47.9% were boys).

Results. Based on the degree of elaboration and originality of the drawings, six qualitatively different Types of productive imagination were identified. The results indicated that the level of imagination in about half of the preschoolers in the senior kindergarten groups was low: these children either did not accept the task at all (we classified them as Type 0) or drew individual objects without any detail (Type 1). Also, the results of the other children (Types 2, 3, and 4) showed that elaboration and originality at the age of 5-6 years developed heterochronically: some children had relatively high scores in one parameter, while others had relatively high scores in another. Less than 5% of the sample showed a high level of imagination development, which was demonstrated by the children using inclusions in their drawings (Type 5). The distribution of Types was similar across the different regions of Russia.

Conclusion. As a result of this study, data and a typology of productive imagination in 6-5-year-old children (pupils of senior kindergarten groups) were obtained, which can be useful to both researchers and practicing psychologists.

Highlights- A typology of productive imagination in preschoolers was created in this study, based on evaluation of two parameters of the drawings made by children according to the “Complete the drawing” technique; they were elaboration and originality. The other two parameters (flexibility and the originality coefficient) were excluded from the analysis, since the originality coefficient’s value strongly depends on the number of children tested in a group (the more children, the higher the likelihood of encountering the same names and pictures, which will reduce the value of this parameter), and the flexibility indicators were high for all the children in the senior groups (more than half of the children received the maximum score for this parameter).

- The main advantage of the typology we developed based on several of the most reliable features of the children's drawings, was that it gave us the ability to unambiguously interpret and evaluate the results of an individual child, which will be useful in both scientific and practical work in child psychology and educational psychology

- Based on our data, girls are more likely than boys to have higher levels of imagination development, a result which is in good agreement with the outcome of our earlier survey of educators on the preschoolers’ level of imagination development. In that survey, educators estimated the level of girls’ imagination development to be significantly higher than the boys’ in the field of fine arts.

Актуальность. Актуальность исследования обусловлена с одной стороны, важностью воображения для познавательного и эмоционального развития детей, а с другой – противоречивыми результатами современных исследований о развитии воображения старших дошкольников.

Цель. Целью исследования выступила оценка и выделение типов продуктивного воображения у воспитанников старших групп детского сада.

Дизайн. Методы. Для оценки воображения была использована методика «Дорисовывание фигур» (Дьяченко, 2007). Рисунки дошкольников анализировались по параметрам гибкости, разработанности и оригинальности. Выборка. Участниками исследования стали 768 воспитанников старших групп детских садов из четырех регионов России (Москвы, Республик Саха и Татарстан, из Пермского Края) в возрасте от 58 до 72 месяцев (из них 47,9% - мальчики).

Результаты. На основе параметров разработанности и оригинальности рисунков были выделены 6 качественно различающихся типов продуктивного воображения у старших дошкольников. Согласно полученным результатам, уровень развития воображения примерно половины дошкольников старших групп низкий: дети либо вообще не принимают задание (мы отнесли их к 0 типу), либо рисуют не детализированные отдельные объекты (1 тип). Также результаты выделения 2, 3 и 4 типов показывают, что разработанность и оригинальность в возрасте 5-6 лет развиваются гетерохронно: у части детей относительно выше оценки по одному параметру, тогда как у части – по другому. Менее чем у 5% выборки был выявлен высокий уровень развития воображения, при котором дети используют включения (5 тип). Было получено схожее распределение типов в разных регионах России.

Вывод. В результате проведенного исследования получены данные и представлена типология продуктивного воображения у детей 5-6 лет (воспитанников старших групп детского сада), которые могут быть полезны как исследователям, так и практикующим психологам.

Ключевые положения- В данном исследовании была построена типология продуктивного воображения у дошкольников, основанная на оценках только двух параметров рисунков, выполняемых детьми в методике «Дорисовывание фигур»: разработанности и оригинальности. Два другие параметра были исключены из анализа поскольку величина коэффициента оригинальности сильно зависит от числа протестированных в одной группе детей (чем больше детей, тем вероятность встретить одинаковые названия и рисунки выше, что будет снижать величину данного параметра), а показатели гибкости были высокие у всех воспитанников старших групп (более половины детей по этому параметру набрали максимальный балл).

- Основным преимуществом полученной нами типологии, основанной на нескольких наиболее надежных показателях детских рисунков, мы видим в возможности однозначно интерпретировать и оценить результаты конкретного ребенка, что будет полезно как в научной, так и практической работе в области детской психологии и психологии образования.

- Согласно полученным данным, у девочек чаще, чем у мальчиков встречается более высокие уровни развития воображения, что хорошо согласуется с результатами проведенного нами ранее опроса воспитателей об уровне развития воображения дошкольников, согласно которому воспитатели оценивают уровень развития воображения девочек значимо выше, чем уровень развития воображения мальчиков в сфере изобразительного искусства.

Introducción. La relevancia de la investigación se debe, por un lado, a la importancia de la imaginación para el desarrollo cognitivo y emocional de los niños y, por otro lado, a los resultados contradictorios de investigaciones modernas sobre el desarrollo de la imaginación en los preescolares mayores.

Objetivo. de la investigación fue evaluar e identificar los tipos de imaginación productiva en los alumnos de los grupos de mayor edad del jardín de infancia.

Diseño. Métodos. Para la evaluación de la imaginación se utilizó un método de «Completar los dibujos de figuras» (Diachenko, 2007). Los dibujos de preescolares se analizaron sobre los parámetros de flexibilidad, elaboración y originalidad. Muestra. Los participantes de investigación eran 768 alumnos de los grupos de mayor edad del jardín de infancia en cuatro regiones de Rusia (Moscú, República de Sajá y Tartaristán, Territorio de Perm) con edades comprendidas entre 58 y 72 meses (de los cuales el 47,9% eran niños).

Resultados. Sobre la base de parámetros de elaboración y originalidad de los dibujos, se identificaron 6 tipos cualitativamente distintos de imaginación productiva en preescolares mayores. Según los resultados, el nivel de desarrollo de la imaginación de aproximadamente la mitad de los preescolares de los grupos de mayor edad es bajo: los niños o no aceptan la tarea en absoluto (los hemos atribuido al tipo 0) o dibujan objetos individuales que no están detallados (tipo 1). Además, los resultados de la identificación de tipos los 2, 3 y 4 muestran que la elaboración y originalidad a la edad de 5 a 6 años se desarrollan heterocrónicamente: algunos niños tienen los puntajes relativamente más altos en un parámetro, mientras otros tienen puntuaciones más altas en otro. En menos del 5% de la muestra se encontró un nivel alto de imaginación en el que los niños utilizan la inclusión (tipo 5). Se obtuvo una distribución de tipos similar en diferentes regiones de Rusia.

Conclusión. Como resultado del estudio, se obtuvieron datos y se presentó una tipología de imaginación productiva en los niños de 5 a 6 años (alumnos de grupos de mayor edad del jardín de infancia), que puede ser útil tanto para investigadores como para psicólogos en ejercicio.

Destacados- En esta investigación se construyó una tipología de imaginación productiva en preescolares, basada en evaluaciones de solamente dos parámetros de dibujos, realizados por los niños en el método de «Completar los dibujos de figuras»: elaboración y originalidad. Otros dos parámetros se excluyeron del análisis porque el valor del coeficiente de originalidad es altamente dependiente del número de niños examinados en un grupo (cuantos más niños, mayor es la probabilidad de encontrar los mismos nombres e imágenes, lo que reducirá el valor del parámetro), y la flexibilidad fue alta entre todos los alumnos del grupo de mayor edad (más de la mitad de los niños obtuvieron los puntajes máximos en este parámetro).

- Vemos la principal ventaja de la tipología obtenida, basada en varios de los indicadores más confiables de los dibujos de los niños, en la capacidad de interpretar y evaluar inequívocamente los resultados de un niño en particular, que será útil para trabajo científico y práctico en el campo de la psicología infantil y la psicología de la educación.

- Según los datos obtenidos, las niñas más frecuentemente que los niños tienen niveles altos del desarrollo de la imaginación, lo que concuerda bien con los resultados de nuestra encuesta de los educadores sobre nivel del desarrollo de la imaginación en preescolares, según la cual los educadores evalúan el nivel del desarrollo de la imaginación de las niñas significativamente más alto que el nivel de los niños en el ámbito de las artes visuales

Origines. L`actualité de cette étude est due, d'une part, à l'importance de l'imagination pour le développement cognitif et émotionnel des enfants, et d'autre part, aux résultats contradictoires des recherches modernes sur le développement de l'imagination chez les enfants d'âge préscolaire plus âgés.

Objectif. Le but de cette étude était d`évaluer et de relever des types de l`imagination productive chez les élèves de grande section de l`école maternelle.

Conception. Méthodes. Afin d`évaluer le niveau du développement de l`imagination on a utilisé la méthode « accomplir des figures » (O.M. Diachenko, 2007). Les dessins d'enfants d'âge préscolaire ont été analysés selon les paramètres de flexibilité, de niveau d'élaboration et d'originalité. Echantillonnage. L'échantillon de l'étude était composé de 768 élèves des groupes supérieurs d`écoles maternelles de quatre régions de Russie (Moscou, les républiques de Sakha et du Tatarstan, la région de Perm) âgés de 58 à 72 mois (dont 47,9 % étaient des garçons).

Résultats. Sur la base des paramètres du niveau d`élaboration et de l'originalité des dessins, 6 types d'imagination productive qualitativement différents chez les enfants d'âge préscolaire plus âgés ont été identifiés. D`après les résultats obtenus, le niveau de développement de l'imagination d'environ la moitié des enfants d'âge préscolaire des groupes plus âgés est faible : soit les enfants n'acceptent pas du tout la tâche (nous les avons classés comme type 0), soit dessinent des objets individuels qui ne sont pas détaillés (type 1). De plus, les résultats de l'identification des types 2, 3 et 4 montrent que le niveau développement et l'originalité à l'âge de 5-6 ans se développent de manière hétérochronique : certains enfants ont des scores relativement plus élevés sur un paramètre, tandis que d'autres ont des scores plus élevés sur un autre. Moins de 5 % de l'échantillon a montré un niveau élevé de développement de l'imagination, dans lequel les enfants utilisent des inclusions (type 5). Une répartition similaire des types a été obtenue dans différentes régions de Russie.

Conclusion. À la suite de l'étude, des données ont été obtenues et une typologie de l'imagination productive chez les enfants de 5 à 6 ans (élèves des groupes de maternelle) a été présentée, qui peut être utile à la fois aux chercheurs et aux psychologues en exercice

Points principaux- Dans cette étude on a élaboré une typologie de l`imagination productive chez les enfants d’âge préscolaire qui n`est basée que sur les scores de deux paramètres des dessins réalisé par les enfants en utilisant la méthode « accomplir le dessin des figures » : le niveau d`élaboration et l`originalité. Deux autres paramètres ont été exclus de l`analyse puisque la valeur du coefficient d`originalité dépend fortement du nombre d'enfants testés dans un groupe (plus il y a d'enfants, plus la probabilité de rencontrer les mêmes noms et images est élevée, ce qui réduira la valeur de ce paramètre) et les indicateurs de flexibilité étaient élevés parmi tous les élèves de grande section de l`école maternelle (plus de la moitié des enfants ont obtenu le score maximum pour ce paramètre).

- Nous voyons l`avantage essentiel de la typologie obtenue, basée sur quelques paramètres les plus fidèles des dessins d`enfants, dans la capacité d'interpréter et d'évaluer sans ambiguïté les résultats d'un enfant particulier, ce qui sera utile dans les travaux scientifiques et pratiques dans le domaine de la psychologie de l'enfant et de la psychologie éducative.

- D`après les données obtenues le niveau du développement d`imagination plus élevé se présente plus fréquemment chez les filles que chez les garçons ce qui est en bon accord avec les résultats de notre précédent échantillonnage des instituteurs sur le niveau de développement de l'imagination des enfants d'âge préscolaire, selon lequel les instituteurs estiment le niveau de développement de l'imagination des filles à être nettement supérieur au niveau de développement de l'imagination des garçons dans le domaine des beaux-arts.

Introduction

One of the most significant new formations of preschool age is imagination, which plays a key role in children’s cognitive and emotional development (Vygotsky, 1982; Elkonin, 1978; Davydov, 1986). According to research results, the preschoolers’ imagination development level is interrelated with their social status in the peer group (Denisenkova, Zvyagintseva, 2013), with reading and writing skills development (Kudryavtsev, 2020) and cognitive activity (Samkova, 2019), which is extremely important for their further successful learning at school (Churbanova, 2009; Bayanova, Khamatvaleeva, 2022). At the same time, many modern scientists express concern about how imagination develops in modern preschoolers, since traditional play, i.e. the main imagination development source (Vygotsky, 1982; Elkonin, 1978; Dyachenko, 1996; Kravtsov, Kravtsova, 2019; Fleer, 2022), begins to be replaced and often supplanted by games on digital devices (Greenfield, 2009; Calvert, Valkenburg, 2013; Veraksa, Kornienko, Chichinina, Bukhalenkova, Chursina, 2021; Belova, Shumakova, 2022; Smirnova, Klopotova, Rubtsova, Sorokova, 2022; Khokhlova, Muller , Savostina, 2022). In this regard, studying the development of imagination in modern preschoolers is a significant and relevant task.

Senior preschoolers’ imagination research review

In this study, we evaluated productive imagination in preschoolers, using the “Complete the drawing” technique, which is a modified version of the E. Torrance test (Dyachenko, 2007). This approach has become widespread in Russia and is now most often used by researchers on preschool development as a tool for measuring the preschoolers’ imagination level (Belkina, & Sivkova, 2017; Denisenkova, & Zvyagintseva, 2013; Samkova, 2019; Morozova, & Polyashova, 2021; Shinkareva, & Gavrilenko, 2018; etc.).

O. Dyachenko proposed to evaluate children’s drawings which were created by completing a drawing of black and white indeterminately shaped figures, regardless of their social or individual novelty, according to parameters which allow them to be compared with the drawings of other children from the selected kindergarten group. The author identified three such parameters: 1) productivity (elaboration) (the correct answers number), which captures precisely the imagination’s direction – that is, its subordination to the task at hand, and not its accidentality; 2) flexibility (the answers’ different categories number), which shows the various possibilities of the children’s answers – i.e., reveals how diverse the objects’ signs can be, based on which the child builds imaginative images, and which he/she transfers from one object to another in his/her imagination; and 3) originality (the response frequency estimation), which reflects the degree of individualization of the children’s creative work.

In O. Dyachenko’s opinion, it is the combination of all three parameters that can express the real novelty of the child’s imaginative images and his/her approach to the task. In addition to these three parameters, the author also proposes to calculate an integral, complex indicator, which is closely interrelated with the three described above; i.e., the originality coefficient, which was calculated as the number of images that are not repeated by the child himself/herself, or in the tasks performed by other children from his/her group.

As a result of studies carried out via this technique, O. Dyachenko identified several imagination Types (or levels) in preschoolers. She classified as Type 0 those children who did not accept the task (refused to do it, or tried, but were unable to complete the task correctly – i.e., either repeated the given example, or drew their own image, not related to the task). Type 1 included children who managed to complete the task, but their drawings corresponded to only one object’s image and were schematic and devoid of details. Type 2 was comprised of children whose drawings also depicted individual objects, but were more detailed; Type 3 included those children who made detailed drawings connected through an imaginary plot; Type 4 included children who finished drawings of figures so that they formed an integrated composition consisting of several objects; and Type 5 (the highest level) was comprised of children, who used a whole new approach – i.e., inclusion, or when the figure becomes a secondary detail of a completely different picture (for example, the triangle in the picture is not the roof of the house, but the lead of a pencil with which a boy draws a picture).

According to O. Dyachenko’s data, children from the senior kindergarten group developed plots with depicted objects, although the originality coefficient gradually decreased. At the same time, Type 5 approaches only began to be used by children in kindergarten preparatory groups (about 1/4 of the group) (Dyachenko, 1996).

Let us turn to more modern data on the preschoolers’ imagination development, which was obtained using “Complete the drawing” technique. A study by N. Denisenkova and T. Zvyagintseva (2013) showed that at the age of 5-6 years (in the senior kindergarten group), children gave a slightly larger number of original answers than the children in the kindergarten preparatory groups, although the image was still built on the basis of the proposed figure and practically always acted as its foundation. Based on the originality coefficient values, the authors found that at 5-6 years old, a high level of imagination development is common for 21.0% of children; an average level for 60.5% of children; and a low level for 18.4% (results were obtained on a sample of 38 children from Moscow). According to the data obtained by the researchers, only after the age of 6 does the image begin to be elaborated through inclusion, a result which is consistent with the data previously gathered by O. Dyachenko (Dyachenko, 1996).

Based on the results of an empirical study conducted by V. Belkina and M. Sivkova (2017) using the “Complete the drawing” technique on a sample of 30 children (15 boys and 15 girls) of 5-6 years old from a preschool educational institution in Yaroslavl, 20% of the children had a low imagination development level, 60% (mainly girls) were at the medium level, and 20% reached the high level. The authors noted the stereotypical nature of most children's drawings, but highlighted that the boys had greater variety in their images; some of the children repeated their drawings in different scenes, without adding details, but explicitly describing their idea, and some, on the contrary, came up with a new image every time and carefully worked it through.

The results of a study by I. Samkova (2019) that employed the “Complete the drawing” technique on a sample of 89 children of 3-7 years old from Moscow, demonstrated, that “by the age of 7, the originality coefficient has a smooth positive trend” (p. 45); inclusions were found in the drawings by approximately 20% of the senior preschoolers.

We observe a completely different picture in the study by N. Shinkareva and A. Gavrilenko (2019) on a sample of 40 children of 6-7 years-old from two kindergarten groups (20 children in each) in Irkutsk. Based on children’s performance using the “Complete the drawing” technique, researchers identified three levels of imagination development in senior preschool age children. They classified 25% of children from one group and 40% from the second group as having a high imagination development level. At a high level, the children produced schematic, sometimes detailed, but, as a rule, original drawings (not repeated by others in the group of children nor by the child himself/herself). The authors mention that in those drawings, the figure to be completed was most often the central element of the picture, which allows us to conclude that inclusion rates are low for these preschoolers.

The authors classified 40% of children from one group and 45% from the other group as having an average imagination level. At an average level, the children finished drawing most of the figures; however, all the drawings were schematic, without details. At the same time, the researchers highlighted lower originality values in children with an average imagination level: there were always drawings repeated by the child himself/herself or by other children in the group. The authors classified 35% of children from one group and 15% from the other group as low level. The researchers regarded children whose tasks were not completed as having a low imagination development level (those children either did not accept the task, or drew something of their own next to a given figure, or made pointless images), as well as those who made schematic, even primitive and stereotypical drawings.

Summarizing the results of the replication studies on imagination development in preschool children carried out by the Department of Preschool Pedagogy and Psychology of the Moscow State University of Psychology and Education in 2016–2018, E. Yaglovskaya (2018) found that only 5% of the examined children in the kindergarten preparatory groups used “inclusion” when working on given tasks, while according to O. Dyachenko, in the last century this approach was observed in 25% of children of this age. That said, the research results showed an increase in the number of original solutions (in comparison with the data of O. Dyachenko). E. Yaglovskaya believes that this fact indicates that the diversity of the subject environment has a positive impact on the originality of children’s imagination. At the same time, the author points out wide data variability of children from different preschool organizations; according to some results, children in the senior group on average produced 1-2 original solutions, and according to others, 4-5. Other data indicate that some modern children use the “inclusion” approach already in middle preschool age, while, according to other data, preschoolers of preparatory age practically do not use it at all.

This remark by E. Yaglovskaya coheres with the contradictory picture of results on the ratio of children with different imagination development levels and characteristics in various Russian studies described above. There are several reasons for such significant discrepancies. First, the small size of the study samples: in most studies, the number of children involved did not exceed 50, which is clearly not enough to be able to draw conclusions about the patterns of imagination development in modern preschoolers. Second, the researchers used different, and not always clear, grounds for identifying the levels, which makes it difficult to compare data. Third, as mentioned by E. Yaglovskaya (2018), such a large scatter of data is often influenced by significant differences in the teaching and upbringing conditions of modern preschoolers in different educational institutions. This situation is well illustrated by the very different results obtained by N. Shinkareva and A. Gavrilenko (2019) in two different groups of the same kindergarten.

Thus, to obtain a more objective picture of the imagination development in modern preschoolers, it is important to conduct a study on a large sample of children in order to neutralize the influence of many additional factors. That is what we attempted to do in our research, the purpose of which was to study the indicators of productive imagination and identify types of imagination development in 5-6-year-old children. The choice of the senior kindergarten groups was due to the fact that, on the one hand, the results of children of this age can be used to judge how the imagination develops, and on the other hand, there is still time (preparatory group) to develop the imagination before the children enter school.

Methods

Sample and Procedure

The study involved 768 preschoolers 58 to 72 months old (M = 65.4; SD = 3.81). Of these, 47.9% were boys. The research participants were students of senior kindergarten groups from four regions of Russia: 24.5% of children from Moscow; 39.1% from the Republic of Sakha; 26.8% from the Republic of Tatarstan; and 9.6% from the Perm Krai.

Each child was evaluated individually by specially trained testers, in a quiet, bright room in the kindergarten where the child was studying. All drawings were photographed by the testers along with the names which the children gave to their drawings. The children's drawings were then assessed by two specially trained experts. After independent evaluation, the results were coordinated.

Methods

To evaluate the preschoolers’ levels of imagination development, the “Complete the drawing” technique was used, which is a modified version of the E. Torrance test (Dyachenko, 2007). The material used was one of the two sets of figures proposed by the author, which included 10 cards, on which one black and white indeterminately shaped figure was drawn (Figure 1). The subject’s task was to complete the drawing of this figure so that a complete image was obtained.

Figure 1. Stimulus material “Complete the drawing” by O. Dyachenko

The results of the tasks were assessed according to three parameters:

-

The images’ originality was measured by the number of the initially given figure’s inclusions in the graphic image. An image was considered original if the initially given figure became an insignificant component of the final drawing. The sum of the drawings in which there were inclusions was calculated.

-

The images’ elaboration was measured by the level of detail – that is, the number of elements finished by the child. This parameter reflected the child’s ability to work out his/her ideas in detail. This indicator was first calculated separately for each image, and then the median was calculated for all drawings of the participant.

-

The imagination’s flexibility was measured by the number of non-repetitive (in terms of the content and principal elements of a drawing) images created by each child. Images in which the figure for finishing turned into the same element were considered identical.

The author of this technique (O. Dyachenko) suggested calculating another parameter, which is considered the most comprehensive indicator of the preschoolers’ imagination development (Dyachenko, 1996), i.e., the originality coefficient: that is, the number of unique images that differ from other drawings of the same child, as well as from the drawings of other children from his/her group, drawn based on the same figure. However, in our research we did not analyze this indicator, since, in the realities of modern life, the number of children in a group varied greatly in different preschool educational institutions.

In our study, for example, the number of children from a kindergarten group participating in the research varied from 5 to 22, while O. Dyachenko herself recommends calculating this indicator with a group size of 25-30 children (Dyachenko, 2007). Such a variation in the number of children in a group affects the value of the originality coefficient: one can expect that the more children in the group, the lower the coefficient will be. In this regard, a comparison of the originality coefficient of two children, one of whom was part of a group of 5 people, and the other in a group of 25 people, appears to be illegitimate and shows the unreliability of this parameter as an indicator of the preschoolers’ imagination development.

Results

As a result of the analysis of the preschoolers’ drawings, a group of 35 children was identified who did not understand the task or could not cope with the tasks’ completion. Their results were not further taken into account. Following O. Dyachenko, we identified them as a separate group (Type) (Dyachenko, 2007).

To further create a typology of imagination development in senior preschoolers, we eliminated the flexibility parameter from consideration due to the very small scatter of data (see Table 1). In addition, more than half of the children scored maximum for this parameter.

Table 1

Means, medians, and standard deviations of scores according to the “Complete the drawing” technique

|

|

M |

Me |

SD |

Max |

Min |

|

Elaboration |

3.09 |

2.50 |

1.791 |

0 |

11 |

|

Originality |

1.24 |

1.00 |

1.229 |

0 |

6 |

|

Flexibility |

9.62 |

10.00 |

0.704 |

5 |

10 |

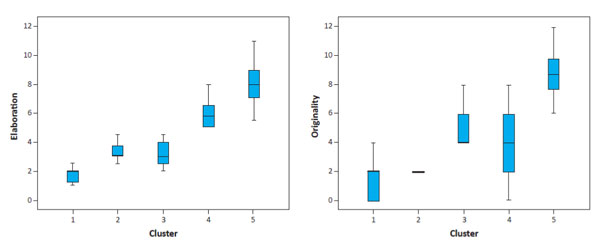

Using cluster analysis (K-means method) based on elaboration and originality scores, the children were divided into five groups (clusters) (see Table 2). The number of groups was determined based both on the theoretical model proposed by the methodology’s author and on the distribution of children among the resulting groups.

Table 2

Cluster Centers, means and standard deviations of Elaboration and Originality scores in each cluster

|

Cluster/ Parameter |

N |

Elaboration |

Originality |

||||

|

Center |

M |

SD |

Center |

M |

SD |

||

|

1 |

299 |

1.7 |

1.69 |

0.491 |

0 |

0.34 |

0.514 |

|

2 |

164 |

3.3 |

3.28 |

0.612 |

1 |

0.79 |

0.411 |

|

3 |

165 |

3.2 |

3.21 |

0.850 |

2 |

2.41 |

0.633 |

|

4 |

70 |

5.9 |

5.89 |

0.835 |

2 |

1.97 |

0.916 |

|

5 |

35 |

8.0 |

8.01 |

1.369 |

4 |

4.20 |

0.933 |

Figure 2 shows diagrams of the range of elaboration and originality scores in the different clusters.

Figure 2. Boxplots of Elaboration and Originality scores in each cluster

Since the number of children in different clusters varied greatly (from 35 to 299) and the distribution of scores for the “elaboration” and “originality” parameters was abnormal within some clusters (Kolmogorov-Smirnov’s test), a nonparametric test was used to assess the differences in these scores between clusters. Applying the Kruskal-Wallis test, we found that both elaboration scores (K-W = 574.487; p<0.001) and originality scores (K-W = 539.672; p<0.001) differed significantly in different clusters.

Comparison of elaboration scores in pairs in different clusters (Mann-Whitney test) revealed the following differences:

a) Children from the 5th cluster had significantly higher scores on drawing elaboration than children from the 4th (U = 210.500; p<0.001), 3rd (U = 0.001; p<0.001), 2nd (U = 0.000 ; p<0.001) and 1st (U = 0.000; p<0.001) clusters;

b) Children from the 4th cluster scored significantly higher than children from the 3rd (U = 0.000; p<0.001), 2nd (U = 23.000; p<0.001) and 1st (U = 0.000; p <0.001) clusters;

c) Children from the 3rd and 2nd clusters did not differ significantly (U = 13014.000; p = 0.542);

d) Children from the 3rd (U = 3643.000; p<0.001) and 2nd (U = 379.500; p<0.001) clusters scored significantly higher than children from the 1st cluster.

Comparison of originality scores in pairs in different clusters (Mann-Whitney test) showed that:a) Children from the 5th cluster had significantly higher levels of drawings’ originality than children from the 4th (U = 112.500; p<0.001), 3rd (U = 408.500; p<0.001), 2nd (U = 0.001; p<0.001) and 1st (U = 0.000; p<0.001) clusters;

b) Children from the 4th cluster scored significantly higher than children from the 2nd (U = 1682.500; p<0.001) and 1st (U = 1727.500; p<0.001) clusters;

c) Children from the 3rd scored significantly higher than children from the 4th (U = 4416.000; p<0.001) and 2nd (U = 0.000; p<0.001) clusters;

d) Children from the 3rd (U = 330.000; p<0.001) and 2nd (U = 13409.500; p<0.001) clusters scored significantly higher than children from the 1st cluster.

Based on the clusters’ comparison, we can describe the resulting Types of children:

0 Type (35 children, 4.6% of the sample). The children failed to complete the task.

1st Type (1st cluster, 299 children, 38.9% of the sample). The children’s drawings included a minimal amount of detail; no inclusions were made.

2nd Type (2nd cluster, 164 children, 21.4% of the sample). The children's drawings were not very detailed; inclusions did occur, but so far, they were rare (on average, 1 picture out of 10).

3rd Type (3rd cluster, 165 children, 21.4% of the sample). The children's drawings were not very detailed, but inclusions were more common than in Type 4 (for all children in at least 2 pictures out of 10).

4th Type The children's drawings were detailed, but inclusions were rare (on average, 2 pictures out of 10).

5th Type (5th cluster, 35 children, 4.6% of the sample). The drawings of these children were highly detailed and demonstrated their ability to make the initial figure an insignificant part of the final composition (the use of inclusions).

The distribution of boys and girls according to the identified imagination Types was also analyzed (see Table 3). Using the χ² test, it was found that gender and imagination Type were associated (χ² = 20.395, p = 0.001, Cramer's V = 0.163). In girls more often than in boys at this age, Types 4 and 5 can be observed, and in boys more often than in girls, Type 1.

Table 3

Distribution of boys and girls by Types of imagination

|

Sex / Type |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

Boys |

17 (4.6%) |

169 (45.9%) |

72 (19.6%) |

76 (20.7%) |

169 (45.9%) |

12 (3.3%) |

|

Girls |

18 (4.5%) |

130 (32.5%) |

92 (23.0%) |

88 (22.3%) |

130 (32.5%) |

23 (5.8%) |

In addition, the distribution of children from different regions of the Russian Federation according to imagination development Types was analyzed (see Table 4). Using the χ² test, we found that region and imagination Type were not related (χ² = 21.291, p = 0.128, Cramer's V = 0.096). We would like to note that in percentage ratio, the Perm Krai had the largest number of children who failed to complete the task (Type 0) and fell into Type 1 (drawings with a minimum of details, without inclusions). In the other three regions (Moscow, the Republic of Sakha, and theRepublic of Tatarstan), the distributions of the identified Types within the samples were very similar.

Table 4

Distribution of children from different regions of the Russian Federation by Type (imagination)

|

Region / Type |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

Moscow |

8 (4.3%) |

56 (35.1%) |

40 (21.3%) |

50 (26.6%) |

15 (8.0%) |

9 (4.8%) |

|

Sakha Republic |

11 (3.7%) |

117 (39.0%) |

69 (23.0%) |

64 (21.3%) |

28 (9.3%) |

11 (3.7%) |

|

Republic of Tatarstan |

9 (4.4%) |

77 (37.4%) |

41 (19.9%) |

45 (21.8%) |

21 (10.2%) |

13 (6.3%) |

|

Perm Krai |

7 (9.5%) |

39 (52.7%) |

14 (18.9%) |

6 (8.1%) |

6 (8.1%) |

2 (2.7%) |

Discussion

The purpose of this research was to study the indicators of productive imagination and identify Types of imagination development in children of 5-6 years old. The need to create a typology arises from a number of factors. First, the original typology by O. Dyachenko was described qualitatively, which raised questions about the universality of assigning a certain level to a child by different testers. For example, if among 10 drawings by a child you can see three different Types at once, how can you correctly draw conclusions about his/her imagination development level? Second, the significant changes that have shaped the preschoolers’ lifestyle over the past 20 years, associated with digitalization, raised questions about how the imagination develops in modern children. At the same time, the typologies presented in the scientific work of recent years were based on small samples, and the authors did not always provide the criteria for assigning children to the selected levels; that resulted in a contradictory picture of data on the development of imagination by modern preschoolers.

The main difference between the typology we created and the typology by O. Dyachenko is the foundation on which the typologies were built. We relied on the two parameters identified by O. Dyachenko (elaboration and originality), while the author - on the way that children create their drawings (i.e., a separate object, a separate object with details, a plot, a plot with the addition of supplementary objects, or the use of inclusion). Both approaches have their advantages and limitations. We see the main advantage of the typology we created in the ability to unambiguously interpret the data of an individual child.

To address the differences between the Types identified by us and modern imagination development typologies: we consider the typology created in this study to be more “appropriate” for the following reasons:

-

The use of only “reliable” parameters (elaboration and originality) allowed us to obtain reliable results, while the originality coefficient cannot always be considered an accurate indicator if the results of preschool children from groups with significantly different numbers of children are compared;

-

Representativeness of the sample (more than 100 children from each of the different regions of Russia participated in the study);

-

Identifying a large number of Types allowed us to see such qualitatively different options for the imagination development as greater detail with low originality (Type 4) and less detail with greater originality (Type 3).

Of course, a typology created on the basis of only two parameters (elaboration and originality), and not on all four identified by E. Torrance, can be considered a certain simplification. However, the two other parameters were excluded from the analysis for objective reasons: the originality coefficient value strongly depends on the number of children tested in one group (the more children, the higher the likelihood of encountering the same names and pictures, which will reduce this parameter), and the flexibility scores were high for all senior groups’ children (more than half of the children scored the maximum for this parameter), which shows the imagination development peculiarities in modern senior preschoolers.

According to our results, the level of imagination development of approximately half of preschoolers in senior groups was low (Type 0 and Type 1). The children either did not accept the task at all, or drew individual objects that were not detailed. The three middle Types we have identified (2, 3, and 4) allow us to conclude that elaboration and originality develop heterochronically (some children have relatively higher scores for one parameter, some for the other), which in the future will be important to check with studies based on other samples (children of more senior and junior ages). Only 35 children (4.6% of the sample) from the senior kindergarten groups showed a high level of imagination development. This result significantly diverges from the data obtained by I. Samkova (2019), which showed the use of inclusion by 20% of senior preschoolers, and from the data by E. Yaglovskaya (2018), which showed that only 5% of the surveyed children of preparatory, rather than senior kindergarten groups, used “inclusion.” We should expect an increase in the percentage of the sample of children belonging to Type 5 who used inclusion in the preparatory group of the kindergarten. It is important to mention that the similar distribution of Types in different regions of Russia suggests that this study was able to reflect the general picture of the imagination development of modern Russian preschoolers.

Our findings that girls have higher levels of imagination development than boys contradict the data of V. Belkina and M. Sivkova (2017), whose research indicated better imagination development in boys, as well as a group of studies in which no significant differences in the imagination development level between girls and boys were discovered (Bobkova, & Kulyamzina, 2011; Baer, & Kaufman, 2008; Holmes, & Romeo, 2013; Barkul, 2009; Alsrour, & Al-Ali, 2014). But, the differences obtained are in good agreement with the results of an educators’ survey on the preschoolers’ imagination development level (Bukhalenkova, Almazova, & Gavrilova, 2023), according to which educators assessed the girls’ level of imagination development to be significantly higher than the level of imagination development of the boys’ in the field of fine arts.

Conclusions

As a result of the research, data was gathered on the development of modern preschoolers’ imagination. Based on this data, more than half of children in the senior kindergarten groups demonstrated a low level of productive imagination development, and only about 5% of children demonstrated a high one.

The study identified six imagination Types in 5-6-year-old children. The typology was based on only two parameters of their drawings – elaboration and originality– since it was decided not to analyze flexibility and the originality coefficient.

Limitations

Among the limitations of this study, we would like to mention the fact that this study dealt with the level of imagination development in only one age group of children – 5-6-year-old students of the senior kindergarten groups. To better understand the whole picture of imagination development at preschool age, it is also necessary to study imagination in children of 3-5 years old and of 6-7 years old. In the future, it is planned to re-assess the imagination of these preschoolers over a year’s time in the kindergarten’s preparatory group, and to identify the dynamics of changes in imagination indicators and the percentage ratio of identified Types.

Moreover, it would be worth monitoring the preschoolers’ mental and speech development level, as well as motor and visual-spatial coordination skills, which could affect the success of children’s creative drawings when performing the imagination technique tasks (Dyachenko, 1996). In the future, it is planned to monitor children’s nonverbal intelligence development level.

We would also like to highlight that this study would be significantly enriched by the use of several different techniques to assess the preschoolers’ level of imagination. By applying the “Complete the drawing” technique, we cannot evaluate some Types of preschool children’s activity: for example, their imagination can also manifest itself in constructing or inventing stories and fairy tales (Bobkova, Kulyamzina, & Evstigneeva, 2011; Kiseleva, & Krivonogova, 2016). The use of several methods would make it possible to see the associations between different Types of productive imagination of preschoolers.

In addition, it would be interesting to compare the created typology with the qualitative characteristics of children’s drawings (such as features of creating a holistic image, as well as the identification of types of cognitive and emotional imagination) (Dyachenko, 1996).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation project No 22-78-10096

References

Alsrour, N.H. & Al-Ali, S. (2014). An Investigation of the Differences in Creativity of Preschool Children according to Gender, Age and Kindergarten Type in Jordan, Gifted and Talented International, 29(1-2), 33-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332276.2014.11678427

Baer, J., & Kaufman, J. (2008). Gender differences in creativity. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 42(2), 75-105. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.2008.tb01289.x

Bayanova, L.F., & Khamatvaleeva, D.G. (2022). Obzor zarubezhnykh issledovanii tvorcheskogo myshleniia v psikhologii razvitiia [Review of foreign studies of creative thinking in developmental psychology]. Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta. Serija 14. Psihologija [Lomonosov Psychology Journal], 2, 51-72. https://doi.org/10.11621/vsp.2022.02.03

Belova, E.S., & Shumakova, N.B. (2022). Osobennosti ispolʹzovaniia tsifrovykh ustroistv kak komponentov semeĭnoi mikrosredy dlia poznavatelʹnogo razvitiia starshikh doshkolʹnikov [Features of the use of digital devices as components of a family microenvironment for the cognitive development of older preschoolers]. Sovremennoe doshkol'noe obrazovanie [Modern Preschool Education], 6 (114), 42-53.

Bobkova, I.K., Kulyamzina, O.V., & Evstigneeva, E.V. (2011). Osobennosti razvitiia tvorchestva starshikh doshkolʹnikov na osnove sochineniia istorii, skazok po metodike Dzhanni Rodari [Features of the development of creativity of older preschoolers based on writing stories, fairy tales according to the method of Gianni Rodari]. Psihologicheskaja nauka i obrazovanie [Psychological Science and Education], 16(5), 38–43.

Calvert, S. L., & Valkenburg, P.M. (2013). The influence of television, video games, and the internet on children's creativity. In M. Taylor (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Development of Imagination (pp. 438-450). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195395761.013.0028

Davydov, V.V. (1986). Problemy razvivaiushchego obucheniia. Opyt teoreticheskogo i ėksperimentalʹnogo psikhologicheskogo issledovaniia [Problems of developing education: The experience of theoretical and experimental psychological research]. Moscow: Pedagogy.

Dyachenko, O.M. (1996). Razvitie voobrazheniia doshkolʹnika [The development of the imagination of a preschooler]. Moscow: Mezhdunarodnyi Obrazovatel'nyi i Psikhologicheskii Kolledzh.

Dyachenko, O.M. (1998). Vozmozhnosti otsenki razvitiia detei starshego doshkolʹnogo vozrasta pedagogami doshkolʹnykh obrazovatelʹnykh uchrezhdeniĭ [Possibilities for assessing the development of older preschool children by teachers of preschool educational institutions]. Psihologicheskaja nauka i obrazovanie [Psychological Science and Education], 3(2), 8-24.

Dyachenko, O.M. (2007). Razvitie voobrazheniia doshkolʹnika. Metodicheskoe posobie dlia vospitateleĭ i roditeleĭ [The development of the imagination of a preschooler. Methodological guide for educators and parents]. Moscow: Mosaic-Synthesis.

Elkonin, D.B. (1978). Psikhologiia igry [The psychology of play]. Moscow: Pedagogy.

Fleer, M. (2022). How Conceptual PlayWorlds Create Different Conditions for Children’s Development Across Cultural Age Periods – A Programmatic Study Overview. New Ideas in Child and Educational Psychology, 1-2(2), 3-29.

Khokhlova, N.I., Muller, O.U., & Savostina, L.V. (2022). Oposredstvovanie produktivnoĭ deiatelʹnosti kak uslovie preodoleniia kompʹiuternoĭ zavisimosti v mladshem shkolʹnom vozraste [Mediation of productive activity as a condition for overcoming computer addiction]. Rossijskij psihologicheskij zhurnal [Russian Psychological Journal], 2(19), 150-160.

Kiseleva, O.I., & Krivonogova, O.A. (2016). Organizatsiia obrazovatelʹnogo protsessa po razvitiiu sposobnosti starshikh doshkolʹnikov sochiniatʹ skazki v sovremennom detskom sadu [Organization of the educational process to develop the ability of older preschoolers to compose fairy tales in a modern kindergarten]. Vestnik TGPU [Bulletin of the TSPU], 12, 13-19.

Kravtsov, G.G., & Kravtsova, E.E. (2019). Voobrazhenie i tvorchestvo: kulʹturno-istoricheskii podkhod [Imagination and creativity: a cultural-historical approach]. Psihologo-pedagogicheskie issledovanija [Psychological and Pedagogical Research], 11(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.17759/psyedu.2019110101

Lee, K.H. (2005). The Relationship between creative thinking ability and creative personality of preschoolers. International Education Journal, 6(2), 194-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332276.2005.11673451

Mi, Sh., Bi, H., & Lu, Sh. (2020). Trends and Foundations of Creativity Research in Education: A Method Based on Text Mining. Creativity Research Journal, 32(3), 215-227. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2020.1821554

Mishchenko, L.V., & Senkova, M.P. (2014). Osobennosti tselostnoĭ individualʹnosti malʹchikov i devochek doshkolʹnogo vozrasta s raznym urovnem razvitiia voobrazheniia v gendernom aspekte [Specifics of integrated individuality of preschool age boys and girls with different level of development of imagination in terms of gender]. Integracija obrazovanija [Integration of Education], 2(75), 1-10.

Morozova, E.V., & Polyashova, N.V. (2021). Studying the imagination of older preschool children. StudNet, 5. [Electronic resource]. Retrieved from https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/izuchenie-voobrazheniya-detey-starshego-doshkolnogo-vozrasta

Paek, S.H., & Runco, M.A. (2017). Dealing with the Criterion Problem by Measuring the Quality and Quantity of Creative Activity and Accomplishment. Creativity Research Journal, 29(2), 167-173. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2017.1304078

Potur, A., & Barkul, O. (2009). Gender and creative thinking in education: A theoretical and experimental overview. ITUAIZ, 6(2), 44 -57.

Robyn, M., Romeo, H., & Romeo, L. (2013) Gender, play, language, and creativity in preschoolers. Early Child Development and Care, 183(11), 1531-1543. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2012.733381

Runco, M.A., Alabbasi, A.M.A., Acar, S., & Ayoub, A.E.A. (2022). Creative Potential is Differentially Expressed in School, at Home, and the Natural Environment. Creativity Research Journal, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2022.2031437

Samkova, I.A. (2019). Psikhologicheskie usloviia razvitiia poznavatelʹnoĭ aktivnosti v doshkolʹnom vozraste [Psychological conditions for the development of cognitive activity in preschool age]. Psihologo-pedagogicheskie issledovanija [Psychological and Pedagogical Research], 11(1), 42—56. https://doi.org/10.17759/psyedu.2019110104

Shinkareva, N.A., & Gavrilenko, A.A. (2018). Osobennosti proiavleniia tvorcheskogo voobrazheniia deteĭ starshego doshkolʹnogo vozrasta s pomoshchʹiu netraditsionnykh tekhnik risovaniia [Features of the manifestation of the creative imagination of children of senior preschool age through non-traditional drawing techniques. ANI: Pedagogika i Psihologija [ANI: Pedagogy and Psychology], 4(25), 68-71.

Shinkareva, N.A., & Shabaeva, V.N. (2018). Ėksperimentalʹnoe izuchenie organizatsionno-pedagogicheskikh usloviĭ i urovnia razvitiia tvorcheskogo voobrazheniia detei starshego doshkolʹnogo vozrasta [Experimental study of organizational and pedagogical conditions and the level of development of the creative imagination of children of senior preschool age]. ANI: Pedagogika i Psihologija [ANI: Pedagogy and Psychology], 4(25), 245-249.

Smirnova, S.Yu., Klopotova, E.E., Rubtsova, O.V., & Sorokova, M.G. (2022). Osobennosti ispolʹzovaniia doshkolʹnikami tsifrovykh MEDIA: novyi sotsiokulʹturnyi kontekst [Features of Preschoolers’ Use of Digital Media: New Socio-Cultural Context]. Sotsial’naya psikhologiya i Obshchestvo [Social Psychology and Society], 13(2), 177-193. https://doi.org/10.17759/sps.2022130212

Veraksa, A.N., Almazova, O.V., & Bukhalenkova, D.A. (2020). Otsenka ispolnitelʹnykh funktsii v starshem doshkolʹnom vozraste: batareia metodik [Assesment of executive functions in senior preschool age: a battery of methods]. Psihologicheskij zhurnal [Psychological Journal], 41(6), 108-118. https://doi.org/10.31857/S020595920012593-8

Veraksa, A.N., Almazova, O.V., Bukhalenkova, D.A., & Gavrilova, M.N. (2020). Vozmozhnosti ispolʹzovaniia igrovykh roleĭ dlia trenirovki reguliatornykh funktsiĭ u doshkolʹnikov [Possibilities of using game roles for training regulatory functions in preschoolers]. Kul'turno-istoricheskaja Psihologija [Cultural-historical psychology], 1, 111-121. https://doi.org/10.17759/chp.2020160111

Veraksa, A.N., Almazova, O.V., Oshchepkova, E.S., & Bukhalenkova, D.A. (2021). Diagnostika razvitiia rechi v starshem doshkolʹnom vozraste: batareia neiropsikhologicheskikh metodik i normy [Assessment of speech development in senior preschool age: a battery of neuropsychological techniques and norms]. Klinicheskaja i special'naja psihologija [Clinical and Special Psychology], 10(3), 256-282. https://doi.org/10.17759/cpse.2021100313

Veraksa, A.N., Kornienko, D.S., Chichinina, E.A., Bukhalenkova, D.A., & Chursina, A.V. (2021). Sviazʹ vremeni ispolʹzovaniia doshkolʹnikami tsifrovykh ustroĭstv s polom, vozrastom i sotsialʹno-ėkonomicheskimi kharakteristikami semʹi [Correlations between Preschoolers’ Screen Time with Gender, Age and Socio-Economic Background of the Families]. Nauka televidenija [The Art and Science of Television], 17(3), 179-209. https://doi.org/10.30628/1994-9529-17.3-179-209

Vygotsky, L.S. (1982). Voobrazhenie i ego razvitie v detskom vozraste [Imagination and its development in childhood]. Collected works. In 6 volumes. Vol. 2. Problems of General Psychology. Moscow: Pedagogy.

Williams, R., Runco, M.A., & Berlow, E. (2016). Mapping the themes, impact, and cohesion of creativity research over the last 25 years. Creativity Research Journal, 4(28), 385-394. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2016.1230358

Yudina, E.G. (2022). Detskaia igra kak territoriia svobody [Pretend play as the territory of freedom]. Nacional'nyj psihologicheskij zhurnal [National Psychological Journal], 3(47), 13-25. https://doi.org/10.11621/npj.2022.0303